César E. Chávez

|

| “Preservation of one’s own culture does not require contempt or disrespect for other cultures.” [1] |

| César Estrada Chávez |

|

Stories can play a vital role in the telling of history. It is the stories, advice and proverbs of his youth that set César E. Chávez on the course to be the spokesman for thousands and role model for millions. César Estrada Chávez was born March 31, 1927, near Yuma, Arizona. His early influences shaped and firmly grounded César in a rich Mexican American tradition. His later life would open him up to new influences that he would use to unite people of many nationalities and beliefs. César always had a strong connection to his family. He was named after his grandfather, who came to the United States in the 1880s. César’s grandfather was a a peasant tied to the land through debt peonage on a Mexican ranch who escaped to the United States in order to secure a better life. César’s grandparents lived on a homestead of more than a hundred acres in Arizona with their fourteen children. One of their children, Librado (which means “freed one” in Spanish) grew up to be Cesar’s father. Librado married Juana Estrada and together they had six children of whom Cesar was the second oldest. Librado worked on the family farm until his 30s. He owned a few small businesses but was rarely able to make much money because they lived in an isolated area and Librado used a lot of his own money to help others. Later, Librado lost his land and the Chávez family moved in with César’s abuelita (grandmother). Mama Tella, as she was called, was to have a profound influence on César. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

|

César’s mother and grandmother taught him a lot about sincerity and charity through their actions. His mother, Juana, set an example of the importance of helping others regardless of their background. Chávez remembered that she “had made a pledge never to turn away anyone who came for food, and there were a lot of ordinary people who would come and a lot of hobos, at any time of the day or night. Most of them were white [nonMexican].”[2] Her kind example modeled for César the charity that many only talk about. His grandmother, Mama Tella, modeled her kindness by sharing her wisdom. She made a point to teach the Chávez children the importance of being a moral person. She did this through stories, advice, and proverbs that always had a moral point. Later on in his life, César remembered his abuelita as someone wise. He said, “I didn’t realize the wisdom in her words, but it has been proven to me so many times since.” [3] Throughout his life, César folded his grandmother’s teachings into his actions and mirrored his mother’s kindness to others. He also reflected their values of ‘practicing what you preach.’ César learned that he could not just tell others how they were supposed to live their lives; he had to do it through his example. Mama Tella made sure that César had a strong religious upbringing. All of the children learned what it meant to be a strong Roman Catholic. She taught them to appreciate the ceremonies and teachings of the Catholic Church. Cesar became a man who relied on his faith to give him strength and direction. He understood that religion unified and strengthened people. One example of a unifying symbol is the Virgin of Guadalupe. For Mexican Catholics, the Virgin represents a unique relationship between the people of Mexico and the Roman Catholic Church. Many Mexican Catholics (and other Latino Catholics) believe that the Virgin appeared to the people of the Americas as an Native American maiden in order to ease and bless their conversion to Christianity. Therefore, for many Mexican Americans, la Virgen de Guadalupe has always been a unifying force. César was always true to his spiritual beliefs; they guided his everyday life as well as his political action. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

|

César heard stories about life in Mexico and about life in the United States after the Mexican Revolution. These stories made an impact on how he would see the world in which he would grow up. César’s family told stories about the unfairness of life in Mexico. They described how hacienda landowners would exploit their workers. He knew that the landowners expected nonstop labor in exchange for the privilege of earning a meager salary. He heard of the easy life that the rich had at the expense of the poor workers. These stories of exploitation of the poor by the rich set the stage for his strong belief in the importance of fairness and justice. Very early, César started believing that the poor were morally superior. He came to that conclusion because he felt that it was the poor that did the majority of the hard physical work. It was the poor that took care of one another when they barely had enough for themselves. To César the poor were the ones who lived a moral life. The stories of injustice did not end at the border. His grandfather told stories about the corruption of politics in El Paso, Texas. Librado would tell stories about his family’s efforts to gain political power in Arizona by voting as a united block of people. César’s father became a leader in the Mexican American community of Arizona. César saw firsthand the power that could come from uniting people. |

| “We need to help students and parents cherish and preserve the ethnic and cultural diversity that nourishes and strengthens this community— and this nation.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

A problem familiar to Mexican Americans was prejudice at school. While in Yuma, Arizona, César discovered what life was like for a student who had grown up speaking and reading Spanish at home. His lessons in prejudice started his first day of school, at age seven, when the other kids started making fun of his accent and called him a “dirty Mexican.” His teachers punished him for speaking in Spanish. At that time, corporal (physical) punishment was allowed in the schools and César discovered that he would get hit for speaking Spanish. He said, “When we spoke Spanish, the teacher swooped down on us. I remember the ruler whistling through the air as its edge came down sharply across my knuckles.” [4] When there were fights on school grounds between Mexican kids and Anglo kids, the teachers and principals always took the side of the Anglo kids. This type of treatment again re-affirmed for César the importance of justice. It also taught him the importance of letting people be themselves. He saw how disheartening it was to be punished for just being oneself. In 1937, César and his family were evicted from their land in Arizona and moved to California as migrant workers. They joined many others going to California during this time of the Great Depression. César experienced firsthand what it was like to wake up at 3:00 in the morning, ride a truck for an hour to get to the fields, work in the sun all day, and then return in the evening after another long ride, only to start over again the following morning. He understood that this type of hard, physical labor resulted in minimal wages and discrimination. He also knew there was no security for the workers and their families. If something happened to the worker, then his family was just out of luck. César grew up knowing the toll that such work took on a person’s body and spirit. César also learned the stories of other cultures and people. When his family began working in California, they worked alongside a multitude of races. César saw that African Americans, Anglo Americans, and Asian Americans all had similar stories of struggle, conflict, and displacement. Throughout his life César made sure that his work helped people of all races to succeed. He saw them as common brothers who could unite. Basically, César grew up understanding that a democracy’s strength comes from a variety of people working together. He never forgot that important lesson. This is one reason why César E. Chávez is not just a Mexican American hero, but a hero to all people. He believed in the strength of the people and he showed it through his actions. As a young boy César learned from his family’s stories, his personal experiences, and the teachings of others. This background, when combined with his experiences during his teenage years, lit a fire in him that would never be extinguished. |

| “It is ironic that those who till the soil, cultivate and harvest the fruits, vegetables, and other foods that fill your tables with abundance have nothing left for themselves.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

During his teenage years, César personally encountered the conditions of the migrant worker. He saw the despair in the migrant camps, he witnessed the exploitation of farm workers, he had to survive on the meager wages, and he experienced ugly racism. He dedicated the rest of his life to combating such conditions and way of life of life. César’s family was always on the move. It is estimated that during the time of the Great Depression and World War II some 250,000 people worked as migrant workers, in California alone. They followed the harvest trail barely earning enough money to live on. They had to spend a lot of that precious money to buy gas to get to the next place of work. It was a hard, insecure life full of hard, physical work. |

|

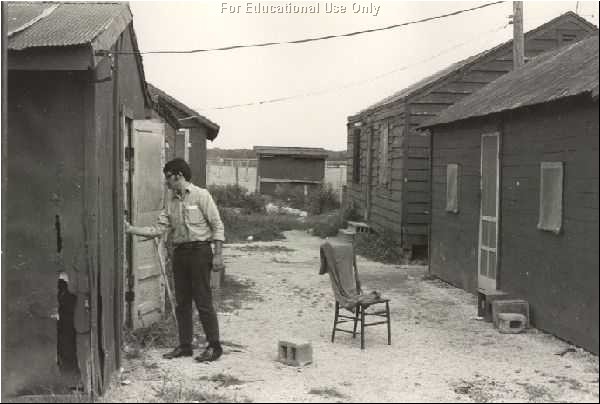

The migrant camps in which they were forced to stay were deplorable. Many camps did not have indoor plumbing and had little electricity. The houses were wood cabins that were drafty and damp. Sometimes the family had to do without cabins and, instead, lived in tents. The companies exploited the workers by charging high rent for their dwellings. The rent was taken directly from their pay. The migrant families had no choice but to stay at these places and buy food and material from company owned stores. |

|

Photo by Cris Sanchez, Courtesy of United Farm Workers

|

|

The migrant workers also had to deal with dishonest labor contractors. A labor contractor is someone hired by a company (in this case the growers) to find workers and oversee them. Unfortunately, many labor contractors were dishonest men, though the companies did not care as long as production continued. Many labor contractors would receive a portion of the profit that they paid the workers. Labor contractors sometimes underpaid the workers and kept the money for themselves. At other times, the contractors would under-weigh the produce in order to cheat the farm workers, or they would not pay the correct taxes and pocket the money instead. Sometimes the workers even had to pay the contractor money for the opportunity to work, since so many people were desperate for employment during this time. César learned these things first hand working as a child in the fields. He had to quit school after the eighth grade because his father had been hurt in a car accident and could no longer work. He had to quit school in order to help support his family. César once recalled the backbreaking work that working in the fields required:

As a result of this experience, one of César’s goals was to make working conditions for the migrant worker more tolerable. |

|

“Years of misguided teaching have resulted in the destruction of the best

in our society, in our cultures and the environment.” “Real education should consist of drawing the goodness and the best out of our own students. What better books can there be than the book of humanity.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

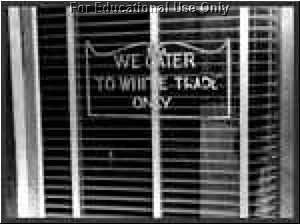

During his teenage years in the 1940s, César encountered ugly racism that made a strong impression on his conscience. César remembers going to a diner where a “White Trade Only” sign was posted. When he ordered a hamburger the waitress laughed at him and said: “We don’t sell to Mexicans.” César was once arrested for sitting in a section of a movie theater not designated for Mexicans. The schools that César attended were also segregated and full of prejudice. César remembers students being made to run laps around the track because they spoke Spanish or being forced to write ‘I will not speak Spanish’ 300 times on the board. Once César even had to wear a sign that said, ‘I am a clown. I speak Spanish.’ These experiences taught César that segregation destroys people’s worth in the eyes of others. Later in his life, he talked about how hurtful this racism was and the scar that it left on his self-esteem, “I still feel the prejudice, whenever I go through a door. I expect to be rejected, even when I know there is no prejudice there.”[6] Throughout his life, César did everything he could to include others, so that they did not feel like outsiders. |

|

Photo from the National Archives

|

|

César grew up in a time when Mexican American youth were trying to distance themselves from the mainstream. Many Mexican American teenagers adopted the pachuco or zoot suit. It usually consisted of a long suit coat with trousers that were pegged (tapered) at the cuff, draped around the knees with deep pleats at the waist, and a low-hanging watch chain. This style of dress became their symbol of individuality. Unfortunately, many other Americans, especially those in the armed forces, saw these pachucos as anti-American. During a brief period in Los Angeles, in 1943, a series of Zoot Suit Riots occurred when American servicemen went around beating up Zoot Suiters In his book Up From Mexico, Carey McWilliams (who was an eyewitness) describes a scene during the Zoot Suit Riots: |

| Marching through the streets of downtown Los Angeles, a mob of several thousand soldiers, sailors, and civilians, proceeded to beat up every zoot-suiter they could find. Pushing its way into the important motion picture theaters, the mob ordered the management to turn on the house lights and then ranged up and down the aisles dragging Mexicans out of their seats. Streetcars were halted while Mexicans, and some Filipinos and Negroes, were jerked out of their seats, pushed into the streets and beaten with sadistic frenzy.[7] |

|

César, like many other Mexican American youth, wanted to escape this world. For many Mexican American men, the only way to escape life in the barrio or the fields was to join the military. César joined the Navy when he was seventeen. He served in the Navy for two years during World War II, then rejoined his family in the fields. However, he was no longer a teenage boy; César was fully ready to become a grown-up in terms of family and union activity. In 1948, César Estrada Chávez married Helen Fabela. César and Helen were partners in marriage and work. Helen quietly supported César in his efforts and provided stability for the family while César was working tirelessly for the cause of the migrant workers. Between 1949 and 1958, Helen and César had eight children. Helen helped to support the family by working in the fields, since César was not paid very well for his work. Helen’s strength can be seen in her response to César as he was preparing to start his own union. César was concerned that his new venture would be too hard on Helen. Her memory: “ … it didn’t worry me. It didn’t frighten me … I never had any doubts that he would succeed.” [8] Helen knew that together they would be able to face whatever life threw at them. |

| “It is possible to become discouraged about the injustice we see everywhere. But God did not promise us that the world would be humane and just. He gives us the gift of life and allows us to choose the way we will use our limited time on earth. It is an awesome opportunity.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

The importance of a union was obvious to César as he was growing up and working the fields. Migrant workers tried to unite in order to get better pay and better working conditions through unions. Most migrant workers wanted better pay for the amount of produce that they helped harvest, fairer treatment on the part of labor contractors, and insurance for accidents. They even had to petition in order to get outhouses and accessible drinking water in the fields. For the companies, these demands cost money—so they did everything they could to avoid paying. Many companies felt that if they gave in to any of the demands by a group of workers, then they would have to meet other demands, as well. Even small improvements would cost a lot of money since they involved thousands of workers and large amounts of land. In addition, many companies felt that the workers’ demands would never be satisfied, so why start on a road that cost money and had no end. So, instead of helping the workers, the majority of companies employed tactics to beat the unions. They asked the courts to prevent the unions from boycotting or picketing. They hired “goons” from other parts of the valley to come in and beat up strikers. They brought in undocumented foreign workers to help to replace picketing workers. They had the police come and arrest the strikers for causing disturbances. Finally, they used the media to make the strikers seem violent and un-American. Since there was anti-communist feeling throughout the country, the companies tried to make the union leaders appear to be anti-American socialists and communists. This is known as “red-baiting” since many communist countries adopted a red flag, the color red will many times represent socialism or communism. People who use red-baiting hoped that the “red” label would cause people to reject the strikers. The red-baiting of César would continue throughout the 60s and 70s. FBI files were kept on César and other leaders of the UFW during these years. |

| César had a number of people as role models for his union activity. The first was his father, Librado, who joined many unions while César was growing up. Another was Ernesto Galarza, who organized many of the strikes during the 1940s in which the Chávez’ family participated. Galarza later served as an advisor to César as he began to form his own union’s leadership. However, his first taste of what it meant to be an organizer was given to him by a Catholic priest. Father Donald McDonnell decided that the physical needs of the migrant workers needed as much nourishment as their spiritual needs. He set about to teach some of the migrant workers about organizing themselves to improve their conditions. He taught them that organizing and bettering themselves went along with the teachings of the Catholic Church. In César, Father McDonnell found a friend and assistant. Father McDonnell saw a lot of potential in César and encouraged him to read. One of the readings that César took on was the Life of Gandhi by Louis Fisher. This book made a deep impression on Chávez and he took the teachings of Gandhi quite seriously, as he would later demonstrate. |

| “When you have people together who believe in something very strongly—whether it’s religion or politics or unions —things happen.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

Through his association with Father McDonnell, César met another man who would strongly influence his life: Fred Ross. While the migrant workers plight was not well known outside of California and Texas, the plight of the inner city Latino was at least given some attention. Fred Ross represented the Community Service Organization whose mission was to help train community leaders to change their own communities. Ross was sent to set up chapters of the CSO throughout California. In his travels Fred asked Father McDonnell if he could recommend some local Mexican Americans to train. César was on the list Father McDonnell provided. After a two hour meeting Fred Ross wrote in his diary, “I think I’ve found the guy I’m looking for.” César ended up volunteering, then working, for the CSO from 1952-1962. César quickly learned how to become an organizer through his involvement with the CSO. He started out as a volunteer helping with voter registration. He was soon promoted to chairman of the CSO voter registration drives. César and his friends signed up so many new voters that they were soon challenged. He was accused of being a communist and was red-baited in the local papers. When César would not back down, he started gaining sympathy and support from neighboring citizens. César quickly recognized the importance of standing his ground even when outnumbered and out-spent. He learned that with time people would recognize the a just cause and support it. César continued to volunteer for the CSO and learned many other valuable lessons, one of which was the importance of helping others in order to establish a bond with them. He later said: “Once you helped people, most became very loyal. The people who helped us … when we wanted volunteers were the people we had helped.” [9] Eventually, Fred Ross was able to hire César as a full-time worker for the CSO, at $35 a week. It is interesting to note that for all his fame and hard work, César Chávez, throughout his life, never made more than $6,000 a year. César became a force within the CSO—his personal experiences and labor training having prepared him to be an effective organizer. In 1958, he got involved in a farm worker’s dispute in Oxnard. César first ordered a sit-down strike in the fields to challenge negative hiring practices by the growers. He also organized the first of many boycotts against the merchants who are selling the product. Chávez also made sure the workers kept meticulous records so that he could use the records to prove what had really happened (instead of relying on hearsay). In addition, the workers picketed meetings, filed formal complaints with the government, and marched with a banner of the Virgin de Guadalupe. It was in Oxnard that César saw it all come together. The use of boycotts, marches, religious images, and political lobbying became associated with César in later years, but it began at Oxnard. The Oxnard experience also taught him that the workers needed to establish formal contracts with the growers in order to keep their hard fought gains. He knew that without a formal union contract, the growers would be free to go back to their usual practices. He felt that the CSO needed to form a union. However, the CSO leadership disagreed with César’s attempts to start one. César continued working for the CSO and, in this capacity, came to see the problems that urban minorities were suffering. Life in the cities for minorities had its own set of challenges and César never forgot that all people needed to be helped. He worked for the CSO for three more years and came to gain many valuable political friendships through his work. One of these early associates was Dolores Huerta, who would one of César’s strongest supporters. Still, his heart was with the migrant worker. The CSO felt that its mission was in the cities; César felt that his was in the fields. In one of many acts of conscience, César decided to do what he felt was the best thing for the migrant workers. He resigned from the CSO and decided to organize farmworkers. |

| “We are tired of words, of betrayals, of indifference … they are gone when the farm worker said nothing and did nothing to help himself … Now we have new faith. Through our strong will, our movement is changing these conditions … We shall be heard.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

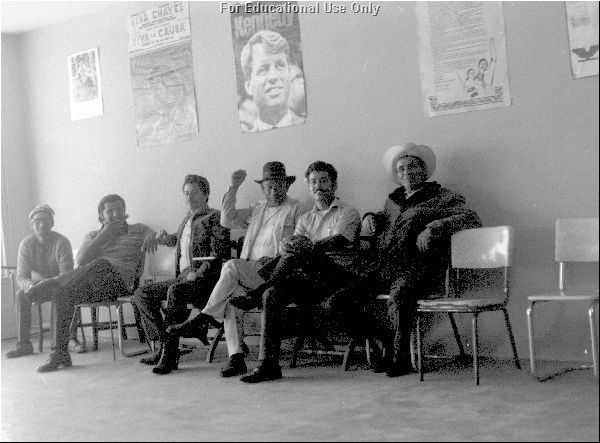

From the (United Farm Workers’) (UFW’s) very beginning, César’s base was Delano, California. It was in Delano that César set up his first headquarters. He chose Delano because there was a year round farming community and because César’s brother Richard lived there and could help out. From Delano, California, the Farm Workers Association was born in 1962. He set about to organize a strong union, knowing that it would be a while before he would have enough of a membership to be effective. He traveled from camp to camp passing out questionnaires and meeting with the workers so that he would know what their needs were. |

|

Photo by Manuel Echavaria

|

|

The first order of business was directly helping the workers. With the help of his brother Richard and the union’s membership, César opened up a small credit union to help the workers weather financial problems. He opened up his home to to farm workers and many would travel to Delano to tell César of the hardships they encountered. Like his mother’s house, the Chávez home was open to all who needed it. Slowly, César started recruiting other leaders to help him. The Reverend Jim Drake, of the California Migrant Ministry (CMM) started working with César and he was able to bring an established ecumenical (many faiths) movement with him. The CMM was made up of Protestant leaders committed to helping the farm workers in the fields. The relationship of these ministers to the workers was very moving to César. He pleaded with the leadership of the Catholic Church to send more priests to the fields to minister to the needs of the workers. Though César was a Catholic, he always believed that the movement should include all others, regardless of race, creed or religion. For the remainder of his life César had strong ecumenical support. César also recruited his cousin Manuel to help (throughout his life César relied on his family to serve as his advisors). César was also able to convince Dolores Huerta to join him once again. It was now time to formally establish the association. On September 30, 1962 the new association, the National Farm Workers Association was established (it later became known as the United Farm Workers). Chávez was elected President, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla vice-presidents, and Antonio Orendain, secretary-treasurer. It was at their first mass meeting that the powerful flag of the union was unveiled. The black eagle and red and white flag became a rallying image for the union and Mexican Americans throughout the United States. That night, Manuel Chávez explained the symbolism behind the flag: The black eagle signified the dark situation of the farm worker. The white circle signified hope and aspirations. The red background stood for the hard work and sacrifice that the union members would have to give. They also adopted an official motto, “Viva la Causa” (Long Live Our Cause). Union opinions would be spread through its newspaper “El Malcriado” (the unruly one).[10] |

|

Photo by Oscar Castillo, Courtesy of César E.

Chávez Foundation

|

| Once the union was well established it begun a series of strikes that would give César national prominence. The workers came to trust César because he managed to help them help themselves. In a news interview with Wendy Goepel, César commented on his commitment to empowering workers. She paraphrased some of his words during the interview as follows: |

| “A Union must be built around the idea that people must do things by themselves, in order to help themselves. Too many people, César feels, have the idea that the farm worker is capable only of being helped by others. People want to give things to him. So, in time, some workers come to expect help from the outside. They change their idea of themselves. They become unaccustomed to the idea that they can do anything by themselves for themselves. They have accepted the idea that they are ‘too small’ to do anything, too weak to make themselves heard, powerless to change their own destinies. The leader, of course, gives himself selflessly to the members, but he must expect and demand that they give themselves to the organization at the same time. He exists only to help make the people strong.” |

| This empowerment was the goal of the UFW. The union had many successes and failures toward this end in its early stages, but its greatest test would come with the Delano Grape Strike that started in 1965. |

|

“We are going to pray a lot and picket a lot.” “There is no such thing as defeat in nonviolence.” “I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

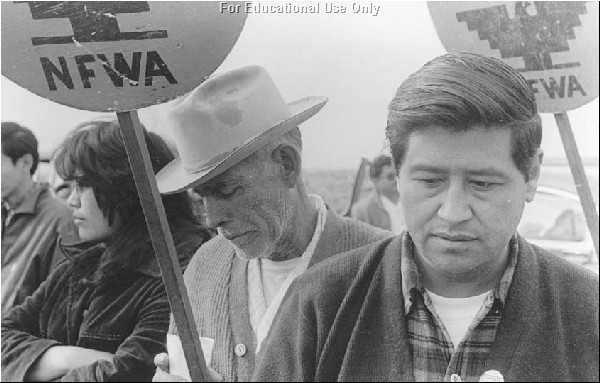

The Delano Grape Strike grew from a small strike to one of national importance. It began with a Filipino organization known as the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) who asked the NFWA to support their strike. Chávez agreed and spent the next days campaigning among the workers to support the strike. César saw an opening to accomplish something major with this strike. A large meeting was scheduled for September 16 (Mexico’s Independence Day). Though there were mostly Mexicans and Mexican Americans in attendance, the hall also contained African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, Arabs and Anglo Americans. [11] After a spirited speech by César, all those attending voted to join the strike. The Huelga (strike) had begun and it involved an area of more that 400 square miles. Soon, the strike took on the look and feel of most other major farm strikes. The ranchers brought in strikebreakers and harassed the picketers. They also tried to intimidate the picketers with shotguns and dogs. They sprayed chemicals on the picketers and had the police harass them. However, the majority of farm workers remained committed to the strike. On the union’s side of the strike, César preached a call for nonviolence. César recognized the spiritual and political power of nonviolence from his studying of Gandhi’s struggle in India and that of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States. César saw the sympathy that nonviolent measures gave to the African American community as it struggled with authorities in the South. Many saw César’s movement as an extension of the nonviolent civil rights movement of the previous decade. It was César’s call for nonviolence that convinced so many to support his political actions and boycotts. César Chávez and Martin Luther King, Jr. were symbols of a nationwide movement for civil rights. Though the majority of César’s actions were intended specifically for the migrant farm worker, he was also concerned about the plight of all people—especially those that were disenfranchised—much like Dr. King before him. As more and more people came to support his strike, César began getting more national attention. César took his message to college students throughout California and the students supported him. Large unions like the United Auto Workers lent their support. Soon came the media. A national TV special, “The Harvest of Shame” showed America the miserable working conditions that the migrant workers had to endure. Reporters from all over the country started coming to Delano to interview César and other union officers. But the highpoint of the strike was still coming. |

|

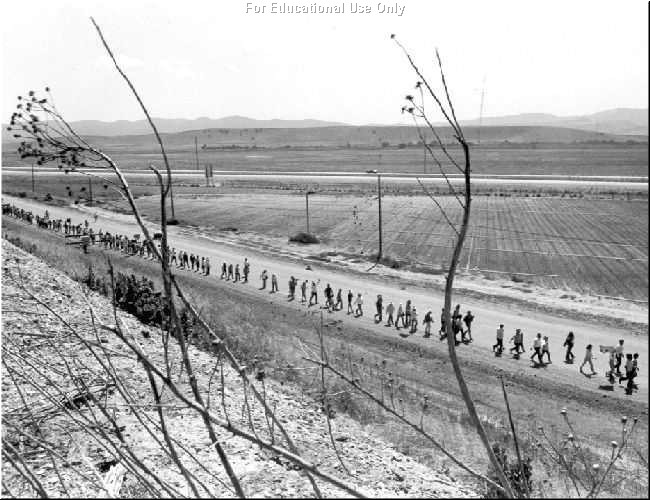

Photo by Cathy Murphy, Courtesy of United Farm Workers

|

| César planned a march from Delano to Sacramento in March 1966. The reason for the march to Sacramento was to get the support of the Governor of California, Edmund “Pat” Brown, while also getting increased exposure to the union’s cause. It was called a pilgrimage because it was as much a unification effort as it was a protest march. César marched the entire way, gathering more supporters the farther he went. The march was a procession of many nationalities, all fighting for the same cause. They carried the banners of the union, the flags of the United States and Mexico, and a flag with the image of the Virgin de Guadalupe. As the march came closer to Sacramento, César was called to an emergency meeting with the head of the grower’s association. The owners conceded to the demands of the Union. The farm workers had won. It was the first union contract between growers and a farm workers’ union in United States’ history. The owners caved-in under the pressure they were receiving from citizens, buyers, and even workers from other areas that supported the strike. A few days later the marchers all celebrated on the steps of the State Capitol. The Governor was not around to greet them but it did not matter; they had won what they had started out for: a real and long-lasting contract. They did it in a spirit of nonviolence and co-operation among people of different races and different religions. It was truly a people’s victory. Though they had achieved their goal, the struggle for continued contracts with other grape growers would remain for many years to come. |

| “You are never strong enough that you don’t need help.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

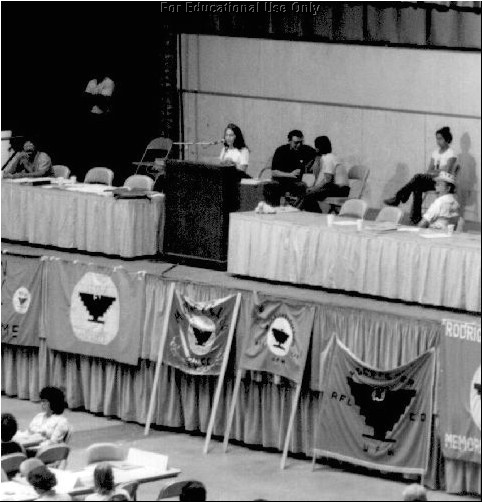

For the next decade, the UFW continued to fight for migrant workers’ rights with the grape growers. They continued to struggle to obtain union contracts with growers. In each action, César and his staff employed the same tactics of boycotts, marches, religious images, and political lobbying. There were also many heated fights for the workers themselves between the Teamsters Union and the UFW. The Teamsters are a national union with millions of members. They fought the UFW for contracts with the growers. The UFW did not want the teamsters to represent the migrant workers because they felt the Teamsters were signing contracts that favored the growers. They felt that the Teamsters did not understand the needs of the workers in the way that the UFW did. For their part, the Teamsters believed that they would be able to use their large union to offer security and a large union’s strength to the workers. The battles for representation of the workers were almost as bitter as those between the growers and the UFW. In the end, the UFW was able to win the majority of battles for representation. These victories came from the combined leadership of César and his close associate, Dolores Huerta. No biography of Chávez’s life would be complete without mentioning his lifelong friend and political ally, Dolores Huerta. Dolores and César worked so well together that it is difficult to separate one from the other in terms of importance to the union. Dolores worked both behind the scenes and as an outspoken and fiery leader. Dolores was a keen organizer and was responsible for much of the policymaking and legislative activity. She wrote speeches, organized rallies, put in countless hours to make sure that events would be successful. She also worked hard to make sure the daily operations of a union were taken care of. The members of the union respected her views and were willing to follow her leadership. She was a powerful woman who helped the migrant workers to see the benefits of uniting under a common cause. Like César, Dolores did not draw lines based on race or religion. She looked for the ability that each individual could bring, regardless of his or her background. One important dimension that she brought to the cause was the importance of treating women as equals. She personified what she hoped society would someday allow: women to be individuals valued for accomplishments. She believed that all people, and each person, have the potential to succeed. She was very influential in helping people achieve success and, therefore, the ability to direct their own lives. The issues and organizational efforts attributed to the UFW are a result of Dolores, César, and other union leaders working together. It would be unfair to attribute all the success to just César because there were many others working together to ensure the success of the movement. Dolores worked alongside César for more than 30 years. She continued her fight for equality through the 1980s and 1990s. In 1988, she was hospitalized after being beaten by a San Francisco policeman during a nonviolent protest rally. She was taken to the emergency room where she was diagnosed with a ruptured spleen and broken ribs. Tapes of the rally showed a policeman severely beating her while she was complying with their demands to back away from the police line. Dolores, like César and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was champion for the civil rights of all people. |

|

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

| “There are many reasons for why a man does what he does. To be himself he must be able to give it all. If a leader cannot give it all he cannot expect his people to give anything.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

During many of the labor struggles that took place after Delano, César began using “the fast” as a way of protesting and speaking up for the injustices that were occurring. A fast is when someone chooses to abstain from eating for a period of time. Sometimes people will go on a water fast which means they will go without eating but will continue to drink water. César went on many hunger fasts throughout his life in order to bring attention to important events. For César, the fast was as spiritual as it was political. César prepared for his fasts by praying and meditating. He often began his fasts without telling anyone, since it was a very spiritual endeavor. Throughout his life, César saw the fast as a spiritual action that would help him overcome his own weaknesses, as well as a force to gather continued support from others. César saw that he could not do all of this work by himself so he hoped that by sacrificing himself he would be able to enlist support from a variety of sources. It is important to remember that, though spiritual, the fasts were also a very effective tactical weapon. They brought national attention and support from millions. People saw a man willing to sacrifice himself in ways that they would not be willing to sacrifice. As a result, they supported him in ways that they could, such as boycotting. Though César’s fasts were politically motivated, it does not mean that they were insincere. They were both. He once said of his fasts, “The fast is a very personal spiritual thing, and it is not done out of recklessness. It’s not done out of a desire to destroy yourself, but it’s done out of a deep conviction that we can communicate with people, either those who are for us or against us, faster and more effectively spiritually than we can in any other way.” [12] In 1968, César went on a 25–day fast that brought national attention to La Causa. The point of his fast was to bring attention to the principle of nonviolence. During one tense strike, some of the members of the UFW wanted to retaliate for violence that was being used against them. César pleaded with the membership to remain committed to the principles of nonviolence for which he and the union stood. 1968 was a turbulent year and it was difficult to convince people everywhere that violence was not the answer to their problems. César did not want this attitude among the union so he told the union leadership that he was going to fast until the members “made up their minds that they were not going to be committing violence.”[13] César knew the importance of this fast. He knew he would have to get the attention of many in order for the fast to have an influence on them so he moved into a storage room at the union’s headquarters. All he had was a small cot and a few religious articles. Soon hundreds were visiting him and holding mass with him on a daily basis. They knew that César was fasting to help them and to bring attention to their needs, not his. César rarely left the small room, but the union was continuing in its work and César was called to testify before a judge about some of the union’s activities. Thousands surrounded the courthouse to offer César their support, since they knew that he needed it in his weakened state. As Chávez struggled to offer testimony, the media began to see the news-worthiness of covering a man so sincere in his efforts that he continued to defend what he believed in even though he was starving himself. Soon, his fast became a national event. Letters of support came from all over the country. Leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy sent him encouragement. The entire country became aware of what César stood for: nonviolence, unity, and La Causa. César decided to end the fast after 25 days. The fast ended with an outdoor Roman Catholic Mass. Although too weak to stand or speak, César had a friend read a message that César had written earlier. It expresses his powerful spiritual reasons for his fast. It read: |

|

“Our struggle is not easy. Those that oppose our cause are rich and

powerful, and they have many allies in high places. We are poor. Our allies are

few. But we have something the rich do not own. We have our own bodies and

spirits and the justice of our cause as our weapons. When we are really honest with ourselves, we must admit that our lives are all that really belong to us. So it is how we use our lives that determine what kind of men we really are. It is my deepest belief that only by giving of our lives do we find life. I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness, is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice. To be a man is to suffer for others. God help us to be men.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

By 1969 Chávez could command a national stage for La Causa. The efforts of the California growers to circumvent the boycotts of specific labels led the union to ask for a national boycott of all table grapes. Grapes became a national symbol of farm worker exploitation and soon people throughout the nation were choosing to boycott grapes. Volunteers began picketing supermarkets that sold grapes. Buying grapes became a moral issue. Many chose not to purchase grapes because they sympathized with the struggle. Others purposely bought grapes to show their support for the growers. However, most sided with the migrant workers and the boycott became a national issue. César was at the center of this movement and was even put on the cover of Time magazine on July 4, 1969. In time, most of the major cities in America (and some in Canada) started refusing shipments of grapes since millions of pounds were rotting because so few people were buying them. As a result, on July 29, 1970 the majority of the grape growers in the region agreed to sign contracts with the union. The UFW had won. It took five years but the union finally achieved its goal of getting contracts with the large majority of growers. The union had won because it used solid union tactics in California; but also because it was able to get the support of millions throughout the United States. The battle of the grapes came to symbolize the power of Americans to unite for a common cause. |

| “It’s amazing how people can get so excited about a rocket to the moon and not give a damn about smog, oil leaks, the devastation of the environment with pesticides, hunger, disease. When the poor share some of the power that the affluent now monopolize, we will give a damn.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

Throughout the 1970s, César E. Chávez and the union continued to fight for the workers on the picket lines and in the political arena. In 1972, the UFW became an independent affiliate (partner) with a large national union—the AFL-CIO. This merger increased the power of the union. The union was also able to use its political muscle to defeat California Proposition 22 that would have taken away much of the political power that the UFW and other unions fought so hard to win. In 1975, the short handled hoe, which required the user to work in such a way that put excruciating pressure on his back, was finally outlawed because of the union’s efforts. However, there were continued clashes with growers and with the unionization efforts of the Teamsters. Though Chávez had the support of many, he was not always able to persuade the politicians and voters to the goals of the UFW. Several California propositions went against his wishes. Government agencies, like the Agricultural Labor Relations Board in charge of labor relations, voted against the union’s demands. Anti-farm labor politicians often appointed members of the Farm Labor Board. For César and the union, there were always victories followed by defeats, but the struggle continued. The UFW boycotts of lettuce and grapes would continue for years, though tied to a variety of different specific issues. Though they lost their share of battles, the migrant worker continued to be better off than before in areas where political pressure was maintained. Even in their losses, the union was at least able to bring up issues that would serve as rallying points in future negotiations. César’s story is not one of always winning; it is one of always struggling for the good. |

| César continued his advocacy for the worker into the 1980s and 1990s. Though union membership fell during these periods, César continued to fight the good fight. This was especially true in terms of fighting against the heavy use of pesticides. In the 1970s, many growers did not want to negotiate with the UFW because it meant they had to respect the union’s strong stance against heavy pesticide use. Other unions were willing to ignore the effects of the pesticides; not the UFW. In 1980, the UFW produced a movie, “The Wrath of Grapes” that showed evidence of the birth defects and high cancer rates the pesticides were causing. Many of the issues that César fought for in terms of pesticide abuses can be found in segments from a speech he gave in 1990: |

| “Many decades ago the chemical industry promised the growers that pesticides would bring great wealth and bountiful harvests to the fields … What, then, is the effect of pesticides? Pesticides have created a legacy of pain, and misery, and death for farm workers and consumers alike … These pesticides soak the fields. Drift with the wind, pollute the water, and are eaten by unwitting consumers. These poisons are designed to kill, and pose a very real threat to consumers and farm workers alike. The fields are sprayed with pesticides: like Captan, Parathion, Phosdrin, and Methyl Bromide. The poisons cause cancer, DNA mutation, and horrible birth defects. The Central Valley of California is one of the wealthiest agricultural regions in the world. In its midst are clusters of children dying from cancer. The children live in communities surrounded by the grape fields that employ their parents. The children come into contact with the poisons when they play outside, when they drink the water and when they hug their parents returning from the fields. And the children are dying … ”[14] |

| César took his crusade against unsafe pesticide use around the U.S. He did everything he could, including fasting, to get support for his cause. In 1988, he went on a 36–day water fast; it was called a “Fast for Life.” Once again, the nation took notice. Supporters rallied around César and put pressure on the companies that were using the strong pesticides. Many politicians and celebrities underwent 3–day mini-fasts to show their support for Chávez. Eventually, César’s strength and determination won out and the growers listened to his concern and began reviewing their use of chemicals. César was still concerned about the use of pesticides before his death; he did not feel that the battle had been won. |

|

Photo by Ann Benson, Courtesy of El Malcriado

|

|

“There’s no turning back … We will win. We are winning

because ours is a revolution of mind and heart … ” “In this world it is possible to achieve great material wealth, to live an opulent life. But a life built upon those things alone leaves a shallow legacy. In the end, we will be judged by other standards.” |

| César E. Chávez |

|

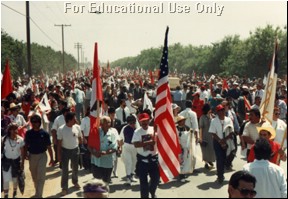

Chávez’s concern for his people continued until the end of his life. He continued to organize political action into the early 1990s. He continued to coordinate strikes and spoke at rallies and colleges, continually spreading the message that the battle for human rights and human safety was not yet over. He battled in the Courts, as growers tried to use legal loopholes like switching ownership rights to void previous contracts with the union. He went from town to town trying to convince consumers not to eat grapes until grapes were pesticide free.[15] César’s body finally gave out in April, 1993. When he died in his sleep, of natural causes, he was in the middle of defending the union in a court action. He was sixty-six years old. His funeral took place on April 29, 1993. More than 30,000 people came from all over the United States to pay their last respects. In his funeral mass, Cardinal Roger M. Mahoney called Chávez, “a special prophet for the world’s farm workers.” |

|

Photo Copyright © Jocelyn Sherman

|

|

César is buried at the UFW’s California headquarters at La Paz and his influence continues to be felt. In 1994, César Estrada Chávez was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United State’s highest honor for nonmilitary personnel. It was accepted by his wife and long time partner, Helen F. Chávez. During the ceremony President Clinton said of Chávez: |

| “Born into Depression-era poverty in Arizona in 1927, he served in the United States Navy in the Second World War, and rose to become one of our greatest advocates of nonviolent change. He was for his own people a Moses figure. The farm workers who labored in the fields and yearned for respect and self-sufficiency pinned their hopes on this remarkable man, who, with faith and discipline, with soft-spoken humility and amazing inner strength, led a very courageous life. And in so doing, brought dignity to the lives of so many others, and provided for us inspiration for the rest of our nation’s history.” |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

Chapter 13: The Legacy of César E. ChávezUnited Farm Workers In 1993, Arturo Rodriguez succeeded César Chávez as President of the UFW continuing the fight for social and economic justice for farm workers and Latinos. Through education and union organizing, the UFW continues to improve living and working conditions for farm workers and other workers. Since kicking off a new field organizing campaign in 1994, a year after Cesar’s death, farm workers—mostly in California—have voted for the union in 21 elections and the UFW has signed 25 new, or first-time, contracts with growers. These employer-employee partnerships include a contract with the nation’s largest berry employer, Coastal Berry Co., covering 750 Ventura County strawberry workers; a contract with long-time UFW adversary, Gallo Vineyards, covering 450 wine grape workers, the first contract in 27 years; and an agreement with Bear Creek Co., America’s largest rose producer, covering 1,400 rose workers. Successes outside California include recent pacts with Chateau Ste. Michelle, Washington state’s biggest winery, and Quincy Farms, the U.S. southeast’s largest mushroom producer in the state of Florida. CECF: César E. Chávez Foundation In 1993, César’s family and friends established the César E. Chávez Foundation to educate people about the life and work of this great American civil rights leader and to engage all, particularly youth, to carry on his values and timeless vision for a better world. The Foundation pursues its mission of education through programs such as the César Chávez Service Clubs, soon to be implemented in high schools across the country, the development of the César E. Chávez Education and Retreat Center, the development of curricular materials on César’s values and principles, and scholarships for students. |

|

Chávez, César E. “The Mexican-American and The

Church.” El Grito, Summer 1968. Chávez, César E. (interviewed by Wendy Goepel). “Viva La Causa.” Farm Labor, Vol.1, No. 5, April 1964. Chávez, César. The Plan of Delano.: Chávez, César E. Statement by Cesar Chavez on the conclusion of a 25 day fast for nonviolence. Chávez, César E. - Tacoma, Washington. “Education of the Heart—Quotes by César Chávez.” “Dolores Huerta Biography.” Clinton, William Jefferson. “Remarks by the President in Medal of Freedom Ceremony” August 8, 1994. Ferriss, Susan and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: César Chávez and the Farmworkers Movement. Paradigm Productions, Inc. 1997. Griswold del Castillo, Richard and Richard A. Garcia. César Chávez: A Triumph of Spirit. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. 1995. McWilliams, Carey.North From Mexico. New York: Greenwood Press. 1968. |

[1] ____. “Education of the Heart—Quotes by César Chávez.” From the UFW Web site. All chapters will begin with quotes from this Web site.

[2]Griswold Del Castillo, page 5.

[3]Griswold Del Castillo, page 5.

[4] Griswold Del Castillo, page 6.

[5] Griswold Del Castillo, page 12.

[6] Griswold Del Castillo, page 13.

[7] McWilliams, page 247.

[8] Griswold Del Castillo, page 33.

[9] Griswold Del Castillo, page 27.

[10] Griswold Del Castillo, page 37.

[11] Griswold Del Castillo, page 43.

[12] Griswold Del Castillo, page 121.

[13] Griswold Del Castillo, page 85.

[14] “Address by César Chávez” Pacific Lutheran University, March 1989

[15] Ferriss and Sandoval, page 247.