|

Let the Spirit flourish and grow; So that we will never tire of the struggle. Let us remember those who have died for justice; For they have given us life. Help us love even those who hate us; So we can change the world.[1] |

| César E. Chávez |

|

“Here was César, burning with a patient fire, poor like us, dark like us, talking quietly, moving people to talk about their problems … We didn’t know it until we met him, but he was the leader we had been waiting for.”[2] In 1965 Luis Valdez, founder of the Teatro Campesino, sensed that César Chávez had the qualities that would lead him to become an internationally known leader in the struggle for economic and social justice for the poor and oppressed. Upon his death in 1993, César Estrada Chávez would be compared to Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, and Mother Teresa--all contemporaries who shared his vision of a world free from suffering and exploitation. Indeed. the legacy of César Estrada Chávez is part of an emerging awareness that began in the last part of the twentieth century. This is the realization that the horrors of war, racism, and oppression can only be ended by a moral code based on nonviolence, love, service, and human compassion. The legacy of César Estrada Chávez is part of a worldwide movement that is working for social and economic justice. César Chávez learned the values that guided him in his struggle to improve the lives of the poorest, the men, women, and children that worked in the agricultural fields. These values came from his cultural background, being a Mexican American born of Mexican parents. He was taught by his family, his friends, and through his own bitter experience. César believed in the importance of self-sacrifice for others, in respecting all races and religions, in the power of nonviolence, and in a divine soul and moral order for the universe. César rejected materialism as a solution to life’s problems and he had a faith in essential goodness of all people. He fervently believed that justice was possible if people were informed about the truth. César Estrada Chávez championed the struggles of all peoples to achieve a better life. His life story reminds us of the courage and sacrifice that it is necessary to bring about social change. We can learn from his example that any achievement of value comes with dedication, tremendous work, and, most of all, triumphal spirit. |

|

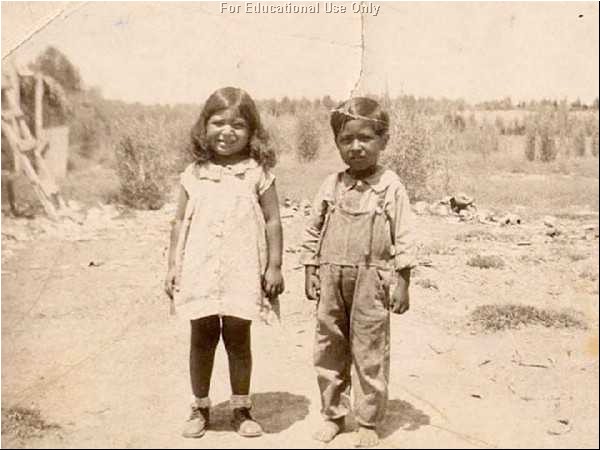

César Chávez’s grandparents, Césario and Dorotea Chávez, came to the United States in the 1880s fleeing the grinding poverty and injustices of the hacienda system in Mexico. They settled near Yuma, Arizona where they established a freight business and homesteaded a quarter section of land. César’s father, Librado, worked with his father on the farm until he was thirty-eight, when he married Juana Estrada. In time, Librado became a small businessman, running a grocery store, a garage, and a pool hall about 20 miles north of Yuma, Arizona. César Estrada Chávez was born there on March 31, 1927. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, the Chávez family was saved from unemployment by a large extended family that provided a built-in clientele for their business. In the midst of the depression, perhaps to increase the family’s security, César’s father decided to expand his business to include a forty-acre parcel surrounding the store. He took out a loan but soon was unable to make the payments and was forced to sell his store. After the loss of their business, the Chávez family moved in with César’s grandmother, Mama Tella, about a mile away from their old store. Chávez remembered life on his grandmother’s farm as a secure and happy time, when he was surrounded by people who influenced his formation as a young man. The most important people in César Estrada Chávez’s early life were his mother and father, and his grandmother, “Mama Tella.” Librado taught César that men should expect to work hard to achieve their goals but they should also always have an open the heart towards others. César’s father was a big man who had inherited the family farm and built several businesses on the property. He believed in strict discipline and yet he was also affectionate and tender towards the children.[3] Librado also taught young César about farm workers unions. When the Chávez family was forced to leave their farm during the 1930s, César’s father led them as migrant workers from field to field and when the wages were too low or the bosses abusive he led them to quit. Young César heard his father and other men talking about strikes at meetings that took place in his home and his father took him to union meetings where César helped clean up afterwards. |

|

Chávez’s mother helped shape his beliefs about nonviolence and morality. She spent a great deal of time with her four children telling them many cuentos (stories), consejos (advice), and dichos (sayings), all of which had a moral point. Chávez later remembered that “her sermons had a tremendous impact on me. I didn’t know about nonviolence then, but after reading Gandhi, St. Francis, and other exponents of nonviolence, I began to clarify that in my mind. Now that I am older I see she is non-violent, if anybody is, by word and deed.”[4] From his mother he learned about sacrifice and giving to others. During the height of the Great Depression she told the children to never turn a person away who asked for food. Chávez’s grandmother taught young César about the richness of their Catholic faith. During the hot summer nights she used to gather the grandchildren around her and tell them stories about the saints and the Bible. From her all the Chávez children grew up with a solid knowledge of their religion. She instilled a love of the rituals of the Catholic Church, the Sunday masses, Christmas and Easter obligations, and special feast days. All his life, César would rely on the spiritual strength he gained from attending Mass. Chávez remembered his family’s influence on his life: |

|

“My mother always insisted that we share with people even when we kids objected because we were hungry ourselves. So I grew up with a very special feeling about the suffering of farm workers and with this faith that I received from my family and from the Church. It came naturally to us to hope for the future and to want to make things better in the world. It seemed so obvious that God wanted more equality and more justice, and that God expected people to work for these things.”[5] |

|

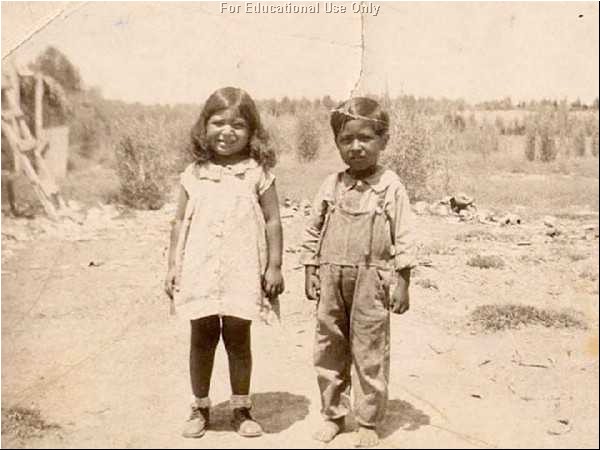

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

While living with Mama Tella on the 160 acres, César and the oldest children experienced their first racial discrimination in school. Like most Mexican American families in the pre-World War II era, they spoke Spanish exclusively at home. César’s uncle taught him how to read Spanish by holding him on his lap and reading aloud from Mexican newspapers. But in the public school, Anglo-American students made fun of the Chávez children’s accents and teachers punished them for speaking in Spanish. Chávez’s school experiences typified those of hundreds of thousands of Mexican Americans in that era. “When we spoke Spanish, the teacher swooped down on us. I remember the ruler whistling through the air as its edge came down sharply across my knuckles.” [6] In these early school years in Yuma, Chávez first encountered racism. Anglo children contemptuously called him a “dirty Mexican;” and when fights erupted between Anglos and Mexicans on the playground, the principal always sided with the Anglo kids. On one occasion, when the teacher heard César describe himself as a Mexican, she insisted that he not use that word. She insisted that he was an American, not a Mexican. Confused, he asked his mother what all this meant. She explained that because he had been born in the United States he was an American citizen. “But I didn’t known what ‘citizen’ meant. It was too complicated.” |

|

Young César’s life, and that of his family, changed dramatically when they lost the family homestead forcing them to join the rural migrant stream flowing west to California. On August 29, 1937, because they were unable to pay back taxes, the State of Arizona took legal possession of their land, although they were allowed to remain there for another year in a vain attempt to raise the money to repurchase the farm. César was ten years old when the Sheriff came to force them off the property. Chávez remembered: |

|

“My mother came out of the house crying. We children [César was 10 at the time] knew there was trouble, but we were confused, worried. For two or three days, the Deputy came back every day … and [then] we had to leave. When we left the farm, our whole life was upset, turned upside down. We had been part of a very stable community, and we were about to become migrant workers. We had been uprooted.” [7] |

|

When the Chávez family left Arizona in 1939, more than 250,000 migrants were in California, remnants of the dust bowl and farm failures of the 1930s. They were a multinational people: poor whites, “Okies and Arkies” from the Midwest, black tenant sharecroppers from the deep South, Mexican immigrants and Mexican American migrants from other southwestern states, dispossessed urban workers of every nationality. Despite their differences in language and background, they shared a daily struggle against insecurity, hunger, and fear. The Mexican and black migrant agricultural workers confronted additional obstacles, racism and ethnic discrimination. Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants had to vie with others for seasonal work. Hardly anyone made the fine distinction of Chávez’s grade school teacher. Mexicans, whether United States citizens, were considered “foreign“ workers, not entitled to the same rights as “American” workers. Thus, racism played an important role in American business by dividing workers and keeping wages down. Some farmers preferred Mexican workers to others because of their reputed docility, and their eagerness to work supposedly made them better able to withstand the fierce heat and backbreaking monotony of field work. [8] On the first night of their journey to California in the old family car, the Chávez family was stopped by a Border Patrol officer who suspected them of being undocumented Mexican immigrants. Although César’s mother had lived in the United States since the age of five months, she did not speak English, and neither did several of his brothers and sisters. After five hours of grueling interrogation in the middle of the desert, the Border Patrol agents let the family go. Others were not so fortunate. During the 1930s, about 500,000 Mexicans were repatriated or deported back to Mexico. “Repatriation” was a polite term for what happened: the majority of Mexican immigrants, whether in the U.S. legally or not, were cajoled, frightened, and intimidated by various federal and local officials into returning to Mexico. This was an attempt to lower the relief roles and to provide more employment for United States citizens by “getting rid of the Mexican.” Many who left were U.S.-born, but had parents who like the Chávezes were long-term residents without papers. The most energetic repatriation campaigns took place in Texas and southern California, where the largest Mexican populations lived. For the next ten years the Chávez family worked as farm laborers, moving from farm to farm up and down California and taking other odd jobs to supplement their income when there was no farm work. During this period, César encountered conditions he would dedicate the rest of his life to changing: wretched migrant camps, corrupt labor contractors, meager wages for backbreaking work, bitter racism. |

|

Working the vegetable and fruit harvest in Brawley, next to the fields in Oxnard, and then up the San Joaquin Valley in the Fall following the cotton crop, the Chávez family was only one of 25,000 to 30,000 migrant families who were always on the move, frequently hungry, just barely able to earn enough money to buy gas to get to the next farm. In Oxnard, the Chávez family was homeless and had to spend the winter living in a tent that was soggy from either rain or fog. They used a 50-gallon can for a stove and tried to keep wood dry inside the tent. The children did odd jobs around town while the adults tried to find work. Moving north to the San Joaquin Valley, they stayed in labor camps where they lived in tiny tarpaper-and-wood cabins without indoor plumbing and with a single electric light. There were no paved streets, and in the winter the ground turned into a slippery quagmire. These conditions were made worse by the exploitive labor contractors who sometimes owned or managed the camps. Some contractors would deduct the workers’ rent from their pay, at exorbitant rates, and he often operated a company store that charged sky-high prices for basic food and supplies. Some contractors would over-recruit workers and then lower the announced wage. Some would short-weight or short-count the sacks or boxes of produce and pocket the difference. Some would make deductions for social security and not report them. Occasionally workers would have to buy their jobs; other contractors would demand sexual favors from female workers. In 1942, César’s father was involved in a car accident and could not work for a month. It was then that César decided to quit school after completing the eighth grade in Brawley, California. César and his older brother, Richard, and sister, Rita, went into the fields to support the family. They thinned lettuce and sugar beets and planted onions in the winter. They worked with the short-handled hoe, a backbreaking instrument. César recalled the inhuman job of thinning: |

|

“I would chop out a space with the short-handle hoe in the right hand while I felt with my left to pull out all but one plant as I made the next chop. There was a rhythm, it went very fast … It’s like being nailed to a cross. You have to walk twisted, as you’re stooped over, facing the row, and walking perpendicular to it. You are always trying to find the best position because you can’t walk completely sideways, it’s too difficult, and if you turn the other way, you can’t thin.” [9] |

|

Later, as a union leader, Chávez would lead the attack to outlaw the short-handled hoe, remembering it from his personal experience and because it caused permanent back injury to thousands of farm workers. The ethnic prejudice that César encountered during this migrant period also shaped his life. When he was age eleven and living in Brawley, he and his brother went into a diner that had a sign, “White Trade Only” in the window. When they ordered a hamburger, the counter girl told them with a laugh, “We don’t sell to Mexicans.” Chávez left in tears, the memory of that laugh ringing in his ears “for 20 years—it seemed to cut us out of the human race.”[10] On other occasions in the San Joaquin Valley, the Chávez family was rejected by Anglo merchants who refused to serve Mexicans. In 1944, in Delano where the family had established a winter base, César challenged the segregated theater system by refusing to sit in the Mexican section. The manager called the police, who dragged him to the police station and held him for about an hour. From these experiences, César learned that segregation was an evil, making people feel excluded and inferior. As a result, one of the main tenants of his later organizing philosophy was that neither racial nor ethnic prejudice had a place within a farm workers union movement. Because of his experiences as a boy growing up in rural California, he would find common ground with the civil rights activists of the 1950s and 60s. Chávez’s migrant period also introduced him to strikes and labor unions. He remembered that he was in “the strikingest family in California” because this father would lead them in walking off jobs where he found them being cheated or exploited. During this period, his father joined several unions including the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU). By being caught up in strikes and union activities, César learned first hand of the difficulties of organizing farm workers, lessons that would help him later on. |

|

In the 1948, along with several thousand Mexican workers, the Chávez family participated in a cotton strike the NFLU organized. One of the NFLU’s Mexican American organizers was Ernesto Galarza, an author, sociologist, and labor expert with a Ph.D. from Columbia University. As a predecessor of César Chávez in organizing farm workers in California, Galarza also organized a consumer boycott against DiGiorgio table grapes. He pioneered the idea of organizing picket lines outside supermarkets to encourage mass support. Later, Galarza acted as an advisor to César during the early years of the UFW strike and boycott. |

|

During the 1940s, César was a young man and, like many Mexican American teenagers of his generation, he flirted briefly with the Pachuco life style. This distinctive subculture flourished among younger Mexican Americans who rebelled against their parents’ conventional values. The Pachucos adopted their own music, language, and dress. The style was to wear a zoot suit, a flamboyant long coat, with baggy pegged pants, a pork-pie hat, a long key chain, and shoes with thick soles. It was a form of rebellion. César remembered, “When I became a teenager, I began to rebel about certain things--the home remedies and herbs my mother used, Mexican music, religious customs … I also got into that trap of thinking (older people) were dull and uninteresting.”[11] When the United States entered World War II, César was working in the fields with his family in the San Joaquin Valley. During the off-season the Chávez family lived in the San Jose barrio of “Sal Si Puedes” (literally “get out if you can;” a phrase capturing the ironic humor of its seasonal residents). About the only way a Mexican youth could escape the barrio and the grinding toil of the fields was to join the armed services. Hundreds of thousands of Mexican American young men joined the military, motivated by patriotism, machismo, or poverty. Finally, in 1944 César joined the Navy, and like thousands of other Mexican Americans, he discovered another world. Arriving in San Diego for boot camp, he found that Mexicans were not the only persons discriminated against because of their nationality or language. He saw that discrimination continued in the Navy with Blacks, Filipinos, and Mexicans being given the lowest jobs. Chávez remembered: “I saw this white kid fighting, because someone had called him a Pollack and I found out he was Polish and hated that word Pollack. He fought every time he heard it. I began to learn something: that others suffered too.” [12] When César got out of the Navy in 1946, he returned to his family home in Delano and resumed work in the fields. César had been in the service for three years and had worked with his family in the fields for two years. He was twenty-one years old and ready to establish his own family. On October 22, 1948, César married Helen Fabela, whom he first had met at La Baratita Malt Shop in Delano when he was 15. Their courtship had taken place during harvest time when the Chávez family was in town. At 21, César was five feet six; a slender, quiet man who seemed shy, almost inconspicuous, to those who met him. He could work long hours, having been conditioned by the monotonous toil in the fields. Darkened by the sun, he had jet-black hair and soft eyes that seemed always to be alert. In turn, Helen was a beautiful woman raised in a migrant farm worker family. Born in Brawley in 1928 of Mexican campesino parents, she was descended from a family that had fought in the Mexican revolution. Her family, like César’s, had become migrant workers during the 1930s and 40s. In the traditional Mexican manner, she was prepared to subordinate her own welfare to that of her family and husband. She became an important partner with César as he began to fulfill his dream of doing something to improve the lot of the farm workers. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

After a brief honeymoon visiting the California Missions, César and Helen moved several times, working in the fields then moving to Crescent City where he worked in a lumber mill, and finally to San Jose where he worked in a lumber yard. Meanwhile, the Chávez family was growing. Eight children came rapidly: Fernando in 1949, Sylvia in 1950, Linda in 1951, Eloise in 1952, Anna in 1953, Paul in 1957, Elizabeth in 1958, and Anthony in 1959. Ordinarily, the financial burdens of supporting this large family would have condemned César and Helen to repeating the cycle of poverty that trapped hundreds of thousands of farm worker families. But events transpired to shape César’s life to be that of a community organizer and then the leader of what would become the nation’s only successful farm labor union. |

|

César Chávez’s introduction to organizing began in 1952 when he met Father Donald McDonnell, a Catholic priest trying to build a parish in the San Jose barrio of Sal Si Puedes. César’s family regularly attended mass in the barrio church and he soon became Fr. McDonnell’s friend and assistant, first doing some work for the small church, then helping with the masses at the bracero camps and the County jail. In the months that followed, César and Fr. McDonnell discussed the history of farm labor organizing in California and the Church’s position on unions. At Fr. McDonnell’s suggestion, César read the Papal Encyclicals on labor and books on labor history; the teachings of St. Francis of Assisi; and Louis Fisher’s, Life of Gandhi. Fisher’s biography made a deep impression on the young Chávez; so much so that he went on to read everything that was available about India’s political and spiritual leader. Mahatma Gandhi’s values struck a responsive cord that echoed in Chávez’s experience. Gandhi spoke about the complete sacrifice of oneself for others, about the need for self-discipline and self-abnegation in order to achieve a higher good. These were values that Mexican farm workers could understand, not only in the life of Christ, but in their own family’s experience. Especially important to Chávez’s moral development were Gandhi’s ideas on nonviolence; they echoed his mother’’s admonitions and teachings. The philosophy of nonviolence later became a major theme in Chávez’s leadership of the farm worker movement. |

|

© 2001 www.arttoday.com

|

|

Another organizer at work in the Sal Si Puedes barrio was Fred Ross, sent to San Jose as an organizer for the Community Service Organization. The CSO was a Chicago-based community empowerment group that sought to train community leaders in poor neighborhoods to bring about social change. In California, the CSO was a Latino organization concerned with issues that affected the urban barrios: civil rights, voter registration, community education, housing discrimination, and police brutality. Fred Ross was a young organizer who had worked managing migrant labor camps during the depression. In the 1950s, he taught himself Spanish and worked for the CSO traveling to the major centers where Mexican Americans lived. When he got to San Jose, he asked Fr. McDonnell to provide him with a list of Mexican Americans who might be good leadership material. On the list was someone named César Chávez; so one afternoon in June 1952, Ross decided to visit his home. César was not at home the first time Ross called, but he left word when he would return. Before Ross knocked at the door again, Chávez went across the street to his brother Richard’s house to avoid him. Months before, several Anglo social scientists had gone around the barrio asking personal questions about the way that Mexicans lived; Chávez wanted no part of this nonsense. Besides, in the barrio, a visiting Anglo usually meant trouble. But Helen felt that this stranger might mean a job or something positive so she pointed Ross to where César was hiding. He crossed the street and knocked on the door; Ross talked to César about arranging for a house meeting with some of his friends so he could explain the ideas behind the CSO. Chávez agreed, but he also had a plan. “I invited some of the rougher guys I knew and bought some beer. I thought we could show this gringo a little bit of how we felt. We’d let him speak a while, and when I gave them the signal, shifting my cigarette from my right hand to the left, we’d tell him off and run him out of the house. Then we’d be even.”[13] But during the house meeting, Ross’ sincerity genuinely impressed Chávez. Ross talked about local concerns as well as the CSO’s advocacy of Mexican rights in police brutality cases. As a result, César never gave the signal, and instead he got rid of the few rabble rousers he had recruited. The meeting lasted two hours. César had been converted. That night Fred Ross wrote in his diary, “I think I’ve found the guy I’m looking for.” [14] |

|

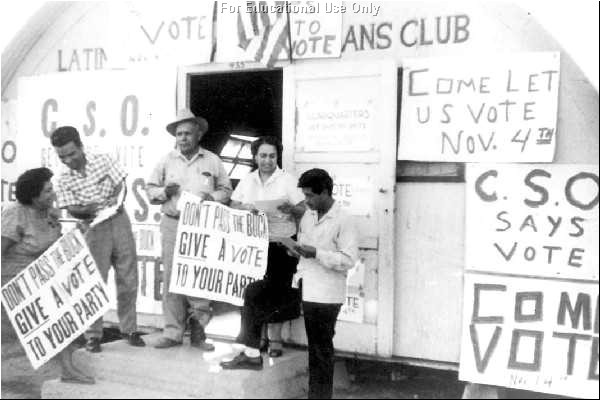

For the next nine years, César Chávez worked with the CSO learning how to mobilize communities and developing friendships and experience that would help him in organizing farm workers. With the CSO, he first encountered the politics of anti-communism called ‘red baiting.’ This was a tactic to accuse minority and progressive leaders of being communists in order to discredit them. César became the chairman of the voter registration drive in San Jose and, working with Fred Ross, they obtained nearly 6,000 new voters. This new development led to a political confrontation with the Republican Central Committee, which feared a Democrat-controlled, Mexican American political bloc. When the Republicans decided to challenge first-time Mexican American voters at the polls, Chávez signed a letter addressed to the State Attorney General protesting the Republican intimidation tactics. In return, the Republicans began to accuse César of being a Communist. F.B.I. agents were summoned to interview him, and stories appeared in the local newspaper implying that he had been influenced by communists. As a result of this controversy, a few of San Jose’s liberals--teachers, lawyers, social workers--began to support César and challenge the innuendos. While weathering the storm, César learned an important lesson: One has to fight back to achieve progress. The experience of fighting against City officials who wanted to prevent Mexican Americans from voting gave Chávez an introduction to the art of confronting institutionalized power. All his work with the CSO was as a volunteer. César continued to work full time in the lumberyard and when he was laid off, he worked full time for the CSO. His first job was to establish a service center where he could help people with their daily problems. In the process, he knew he would establish a network of people who felt obligated to the CSO. The experience of building the service center taught César an important lesson that became the foundation of his organizing style: Helping people and expecting their help in return was a way to build a strong organization. As he said later, “Once you helped people, most became very loyal. The people who helped us back when we wanted volunteers were the people who we had helped.”[15] Soon Ross promoted Chávez to be a full-time organizer paying him $35 a week. He was assigned to a voter registration drive in southern Alameda County in DeCoto (today Union City). After this successful drive, the CSO made him a statewide organizer and sent him to a series of small towns throughout the San Joaquin Valley: Hanford, Salinas, Visalia, and many others. The CSO increased his salary to $58 a week, but every two or three months he and his family had to move to a new assignment. |

|

In the small rural town of Madera, Chávez encountered more anti-communist paranoia. He was working with a local Pentecostal preacher to get Protestant Mexicans in Madera to join the CSO. Using songs to rally people, the preacher and César were successful and got about 300 people to attend regular meetings. The local Mexican American middle class grew fearful that this outsider was taking over their traditional power base. Soon they held a secret meeting of the CSO Executive Board to condemn Chávez as a communist. Chávez countered by calling a special meeting of the membership and replacing the board with farm workers, all of whom were Spanish-speaking and Protestant. The appeal to the workers for their support ended the power play and gave César another political lesson in organizing--the most important supporters are the everyday workers; the middle class cannot always be trusted to support grassroots organizing. |

|

The CSO gave top priority to organizing urban Mexican Americans; farm workers were not on the agenda but César hoped that eventually they would be. In 1958, he finally got a chance to organize farm workers with the CSO when the organization sent him to Oxnard, California to support a local labor union strike among the lemon workers who were being hurt by illegal use of braceros. The Bracero Program had been started during World War II to help growers with labor shortages, allowing them to import contract farm laborers from Mexico. The growers liked the Bracero Program since they used braceros to break strikes and to lower wages, and they could dispose of them when they were done. The program lasted until 1965. . During the beginning of the farm worker movement, Cesar fought to dismantle the Bracero Program, cutting off the source of expendable cheap labor in order to organize more effectively. When he arrived in Oxnard, César found that local residents were concerned about braceros taking their jobs. They thought that local residents should be given preference in hiring for agricultural jobs. In fact, the Bracero Program’s regulations stipulated that the braceros could not be used to replace the local work force; there had to be a certified labor shortage. When Chávez began helping local residents to resolve the problem, he found a corrupt system that was controlled by the growers in league with state and federal officials. The growers falsely claimed the existence of labor shortages, then exploited the braceros by recruiting many more than were needed, giving them only occasional work at lower pay while charging them inflated prices for room and board. Chávez decided to attack this injustice on many fronts. First, he got CSO and community members to apply for work every day with the Farm Placement Service and compiled records of their applications and rejections. Next, the CSO organized a boycott of local merchants to protest their support of the system and to pressure them to change it. Then César organized sit down strikes in the fields to challenge the hiring of braceros. The farm workers picketed a meeting of the Secretary of Labor James Mitchell, when he came to Ventura for a talk. They marched with a banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe to protest the lack of jobs for local residents. They pressured the Farm Placement Service office with hundreds of complaints, and they lobbied the state government offices. The outcome of this intensive campaign was a brief victory. Finally, the state officials fired the Farm Service Placement director and some of his staff, and they started hiring hundreds of people who lined up outside the CSO headquarters every day. The experience in Oxnard was pivotal for Chávez. He experienced tactics such as the boycott, the march, the use of religious images, and political lobbying. These strategies later became standard techniques during the many struggles of the United Farm Workers Union. He also realized where his life’s work lay—in helping the powerless gain dignity. After the Oxnard campaign, Chávez was reassigned to Los Angeles and appointed the National Director for the CSO. He and Helen moved to East Los Angeles and they continued with his organizing knowing that eventually the CSO would have to endorse working with farm workers or else he would have to leave. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

While working with the CSO, César got to know key people who would be important for his work with the United Farm Workers union. One of the key people was Dolores Huerta who, when she joined the CSO, was a divorced housewife with several small children. An attractive woman originally from New Mexico, she was completing a college degree. She was outspoken even when her views differed from those of male leaders. This dynamic, intense, fast-talking, and alert woman was assertive and aggressive. She did not fit the traditional stereotypes of a Mexican mother. In the years that followed, however, she became an indispensable lobbyist and political leader within the farm workers movement. Another CSO member who met Chávez during these years was Gilbert Padilla. He became one of the founding members of the farm workers union. Padilla joined the CSO after hearing Chávez talk one night about the problems of farm laborers and how they should work together to improve their conditions. The next week Gilbert traveled with Chávez when he spoke in the barrio. Chávez served as the Executive Director of the CSO for two years. He hired both Padilla and Huerta as organizers. When César was working for the CSO in Los Angeles, he became familiar with big city problems and politics. In 1960, the CSO worked with the Viva Kennedy Clubs, a movement organized by the Democratic Party to register voters among the Spanish-speaking Catholics in the urban barrios. As the CSO Executive Director in Los Angeles, Chávez met and worked with the founders of Mexican-American Political Association (MAPA): Eduardo Quevedo and Bert Corona. They had established a political association in 1959 to advance the Chicano community’s political interests in the state. The CSO, MAPA, and the Viva Kennedy Clubs in the early 60s became important training grounds for young Mexican Americans who were beginning to self-consciously call themselves “Chicanos,” a slang term natives had used for decades to denigrate newly arrived Mexican immigrants. Finally in 1962, the CSO had its annual convention in Calexico, California, a border town in the Imperial Valley and entry point for thousands of migrants from Mexico. During the convention, Chávez proposed that the CSO support a union movement for farm workers but to his disappointment the convention voted it down arguing that the CSO was not a labor organization. After this, César decided to resign and devote himself to building an independent farm workers union. Before his decision, he talked to Helen and she encouraged him. She remembered: “[César] did discuss it and say that it would be a lot of work and a lot of sacrifice because we wouldn’t have any income coming in. But it didn’t worry me. It didn’t frighten me … I never had any doubts that he would succeed.” [16] Soon after César’s resignation, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) offered him a salaried job as an organizer, but he turned them down because he wanted to work with “no strings attached.” So in the summer of 1962, he, Helen, and their eight children traveled to Carpinteria Beach, near Santa Barbara, and took a brief camping vacation to plan their future. They had about $900 in savings, and César could draw unemployment insurance for a time. They decided to use Delano as a home base for organizing their union. There, Richard (César’s brother) lived and was head of the local CSO and, if necessary, they could move in with him. Helen and César knew there was a permanent, year-round farm labor community in Delano. That could be a solid base for a farm worker organization. |

|

For the next three years César visited hundreds of small labor camps and towns in the San Joaquin Valley trying to recruit members for a new farm workers union. Meanwhile, Helen got a job in Delano picking grapes, and, when he returned from his trip, César worked at a temporary job picking peas. They found a cheap rental on Kensington Street in Delano and César used the garage for his headquarters. Past failures of unions and strikes had made the farm workers afraid of unions so César decided to call his organization the Farm Workers Association to avoid using the term “union.” He resolved to be patient and build a strong organization before challenging the agribusiness corporations. Using his CSO training, Chávez decided to emphasize the service-providing functions of his organization. He traveled extensively, talking to the workers to see what they thought about a union and the services it should provide. Traveling out into the fields and into the camps and colonias, he passed out more than 80,000 questionnaires and talked to thousands of workers. César found them reticent to speak while in the fields, so he met with them at night, in house meetings, where they were more open about their feelings. Chávez organized a modest burial insurance program and a credit union to provide for members with financial emergencies. The funding for these projects came from the members themselves A little later, César and Helen set up a co-op to sell tires and auto supplies at cost. Helen began to work full time for the association as the accountant and administrator of the Credit Union. Soon the word spread that this new organization would help farm workers with a variety of practical problems such as nonpayment of wages, late welfare checks, claims for workman’s compensation, and difficulties with the County hospital, with the schools, or with the INS. Scores of farm worker families traveled to Delano to tell César of their plights. His house was available to them day or night, seven days a week. By 1962, Chávez had begun to assemble a working team that functioned like a second family. One important addition was the Reverend Jim Drake. A Protestant minister who worked with the California Migrant Ministry (CMM), Drake was an intense young seminarian with a passion to reform the migrant working conditions. Because of the CCM, Chávez gained important staff members and economic support for his fledgling association. Reverend Drake became César’s stern-faced, impatient, administrative assistant, traveling with him from town to town as they built the association. César also recruited his cousin, Manuel Chávez, who was working as a car salesman in San Diego. Manuel had grown up with the Chávez family and had worked in the fields with them. César convinced Manuel to quit his job and to move to Delano on a trial basis for six months. After the six-month period, Manuel decided to stay, becoming one of César’s closest associates for the next decade. César also talked Dolores Huerta into quitting her job with the CSO and moving to Delano where she and other union volunteers were fed and housed by farm worker families. The union grew, nourished by personal sacrifice. Indeed, the Chávez family at times had to go without food and clothing to pay for union expenses. César and Manuel were reduced to asking barrio residents for food. They found that in accepting this humble hospitality, they created a bond of trust that brought in new members. In this way they met Julio Hernandez, a farm worker from a small colonia near Corcoran, who became the first full-time staff volunteer for the union. The goal was to hold an organizing convention for the union. Together, César, his cousin Manuel, Jim Drake, Gil Padilla, Dolores Huerta, and Julio Hernandez worked through the summer of 1962, visiting house meetings to ask farm workers to send representatives to a meeting that would formally establish the UFWA. On September 30, 1962, about 150 delegates and their families came to an abandoned theater that Manuel had rented. The official name of the new organization was to be the National Farm Workers Association. The delegates likewise voted for the union’s officers and elected César Chávez President and Executive Officer; Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla became the Vice Presidents, and Antonio Orendian the Secretary-Treasurer. They voted to have dues of $3.50 a month, a considerable sacrifice for farm workers. In one dramatic moment during the conference, Manuel Chávez unveiled a huge copy of the union flag that he had designed. At first the colors and the symbol seemed too radical, too bold, too provocative. After some discussion, the representatives voted to accept the flag as the official emblem of the association, and they adopted the official motto, “ Viva la Causa.” This slogan or “grito“ eventually became universally known, echoing the aspirations of a new generation of Mexican Americans in the fields as well as urban barrios. It was a cry for justice long over due. |

|

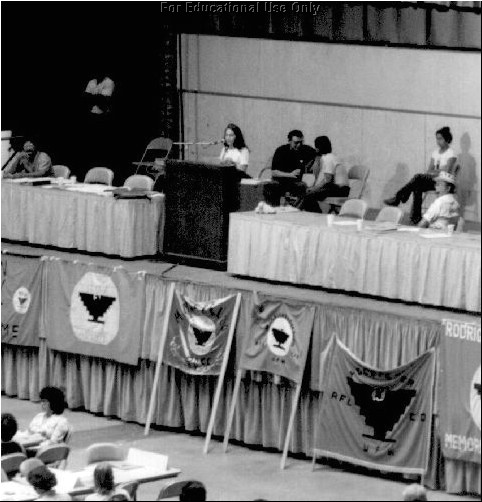

Photo Copyright © Jocelyn Sherman

|

| In early 1965, the National Farm Workers Association had its first strikes, one by flower workers in McFarland and another of migrant workers to protest increases in their rent. Both strikes were relatively short and resulted in some success. César guessed that the union would not be ready for a sustained strike for another three or four years. He could not foresee that in September 1965 circumstances would force him and the new union to initiate the longest and most successful agricultural strike in American history. |

|

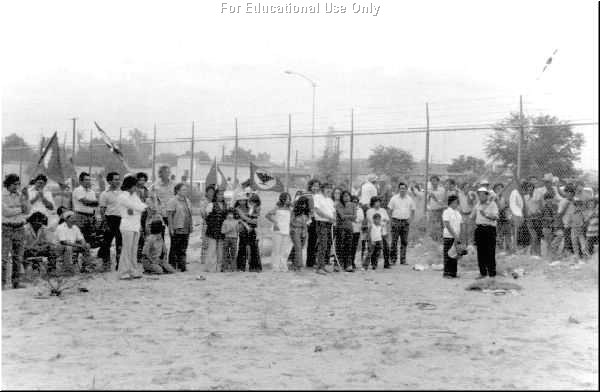

The 1965 grape strike in Delano grew out of a protest by Filipino farm workers over wage inequities. They were being paid less than bracero workers. Early in the season, AWOC organized a strike to protest this and, after ten days, they won a raise for both Mexican American and Filipino workers. Later in the summer, the grape harvest moved north into the San Joaquin Valley and growers continued to lower the rate for non-bracero workers. On September 8, 1965 in Delano, the AWOC Filipino members led by Larry Itliong began a strike against the local growers, demanding wage parity. Police began to harass the strikers, and growers evicted Filipinos from their labor camps. Those who were evicted asked César and the Farm Workers Association for support, and for a promise to respect their picket lines. To decide whether to join the Filipinos on strike, Chávez called a meeting of the union members at Delano’s Catholic Church’s social hall on September 16th, Mexican Independence Day. That evening more than 500 farm workers and their families met in an emotional revivalist atmosphere. Chants of “Viva La Causa!” echoed before and after the speeches of various supporters for the strike. The hall was filled with people of all nationalities and races; Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, Arabs, and Anglos, but Mexicans predominated. Chávez spoke at the meeting. |

|

“You are here to discuss a matter which is of extreme importance to yourselves, your families and all the community. … A hundred-and-fifty-five years ago, in the State of Guanajuato in Mexico, a Padre proclaimed the struggle for liberty. He was killed, but ten years later Mexico won its independence. … We Mexicans here in the United States, as well as all other farm laborers, are engaged in another struggle for the freedom and dignity which poverty denies us. But it must not be a violent struggle, even if violence is used against us … The strike was begun by the Filipinos, but it is not exclusively for them. Tonight we must decide if we are to join our fellow workers in this great labor struggle … ” [17] |

|

Other farm workers rose to speak and added their stories of misery and suffering to the call to join the strike. Representatives of various states in Mexico rose to pledge their support. Chávez explained the sacrifices they would have to make during a strike; the union did not have a strike fund, and it would be a long struggle. Nevertheless, the worker shouted again and again, “Viva la causa! Viva César Chávez! Viva la union!” |

|

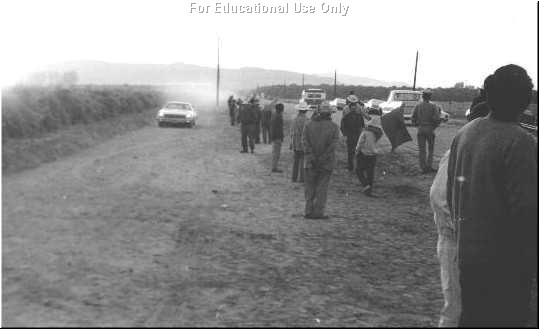

The Delano grape strike covered a 400-square mile area and involved thousands of workers. The job of organizing picket lines to patrol the fields fell to inexperienced farm workers and urban volunteers who worked side by side. The sheer dimensions of the ranches and farms made it impossible to constantly maintain pickets at all the entrances. Inevitably, scab workers, who were hired to take the jobs of the strikers, found their way into the fields and the union had to find a way of convincing them to join the strike. The picket line then became a noisy place. The picketers cajoled, argued, pleaded, orated, and shamed the field workers in Spanish, Tagalog, and English trying to get them to join the strike. Picketers walked the dusty borders of the fields holding hand painted signs saying “Huelga,” “Delano Grape Striker,” “Victoria!” accompanied by the NFWA black eagle. As always, they were closely observed by the police ready to arrest those entering the ranch property. Sometimes the ranch foreman and his staff would harass the strikers, revile them with oaths and foul language, try to provoke them into crossing over onto ranch property. Later, some growers hired goons, recruited from the cities, to intimidate the strikers. Violence was a frequent occurrence. Some ranch foremen raced their pickup trucks up and down the lines at top speed. Some drove their tractors between the pickets and the fields to choke them with dust. Some sprayed them with chemicals and intimidated them with shotguns and dogs. Sometimes they succeeded in injuring strikers, but when someone got hurt on the picket line, it often had the effect of provoking a sympathy walk out by their own workers. The police almost never intervened to protect the picketers. They photographed the strikers and copied license plate numbers of the picketers’ cars. They arrested picketers for disturbing the peace when they shouted “Huelga!” The police were clearly in support of the growers. |

|

Photo copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

|

During the early days of the strike, hundreds of volunteers descended on Delano to participate in the strike. Many were clergy, responding to the message of the new liberation theology. Churchmen from the Migrant Ministry arrived and reported that there was growing church support for the strike Priests from barrio parishes came to offer help from the inner city. Father Victor Salandini volunteered to be a lobbyist in Washington D.C. Other volunteers who offered their services as legal consultants and public relations experts. The Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality sent messages of support and eventually volunteers. César was concerned when Chicano activists began arriving and tried to convert the farm worker movement into a movement of La Raza, promoting a Chicano political agenda. In his words, “…When you say la raza you are saying an anti-gringo thing, and our fear is that it won’t stop there. Today it’s anti-gringo, tomorrow it will be anti-Negro, and the day after it will be anti-Filipino, anti-Puerto Rican. And then it will be anti-poor Mexican, and anti-darker-skinned-Mexican.… On discrimination, I don’t even given the members the privilege of a vote, and I’m not ashamed of it. No. The whole business of discrimination can’t exist here.”[18] One of the early student volunteers to join the strike was a young Chicano from the bay area named Luis Valdez. Originally from Delano, he had grown up in a migrant family but had escaped from the fields to the city and became a university student and member of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. He brought a creative energy to Delano that soon resulted in the organization of El Teatro Campesino (The Farm Workers Theater). Valdez had the idea of using simple one-act skits, called actos, to educate farm workers about the union and the issues involved in the strike. The Teatro, performing on the back of a flat bed truck in the fields, was an effective way of reaching farm workers. The actos were improvisations that dramatized, often in uproariously funny and ironic ways, the lives and struggles of field workers. In Delano, Valdez set up Centro Campesino Cultural, a Farm Worker Cultural Center, to teach migrant children about their Mexican heritage through art, music, dance, and teatro. Luis stayed with the UFW for several years and then moved his group to San Juan Bautista where they continued to produce plays and movies. Ultimately, Valdez broke into Hollywood with his stage production of “Zoot Suit“ and the movie “La Bamba.” César’s main activity during the early months of the strike was to travel around the state to the various college campuses to give speeches and galvanize support for the striking farm workers. Chávez’s speaking style had changed very little from his CSO days. He was not an emotional speaker. He convinced students to support the union through his sincerity, humility, and command of the facts about the struggle between the farm workers and the growers. His “low key“ approach was disarming in an age of radical and flamboyant rhetoric. Chávez spoke about how the farm workers were fighting for their civil rights and economic justice. The farm worker movement dovetailed with a growing national concern with civil rights. Publicity became increasingly important when the union decided to launch a boycott to put pressure on the growers to recognize the union and sign contracts. They targeted the most identifiable grape products from the largest Delano growers, Schenley Industry, the DiGiorgio Corporation, S&W Fine Foods, and Treesweet. The success of the boycott depended on an informed and sympathetic consumer. In Chávez’s eyes, the boycott would rely on the sense of justice of all people: “Our boycotts are predicated on faith in the basic compassion of people everywhere. We are convinced that when consumers are faced with a direct appeal from the poor struggling against great odds, they will react positively. The American people still yearn for justice. It is to that viewpoint and that yearning that we appeal.”[19] |

|

From the beginning of the strike, Chávez emphasized the importance of nonviolence as a strategy. He exhorted the volunteers and picketers: “Non-violence is more powerful than violence. We are convinced that non-violence supports you if you have a just and moral cause. Non-violence gives the opportunity to stay on the offensive, which is of vital importance to win any contest.” [20] Chávez’s faith in nonviolence came from his mother’s influence, his religious faith, and his self-education in reading Gandhi and other pacifists. In 1965, nonviolence was a practical tactic for rallying national support for a labor strike. Nonviolence was an important characteristic of Martin Luther King’s leadership of the civil rights movement, and it was fast becoming a tactic of the anti-war movement, although in both these cases nonviolent protests would increasingly escalate into violent confrontations. For Chávez, nonviolence meant time consuming organization and training. He used Gandhi’s phrase “moral jujitsu“ to describe its effect on the opposition. Chávez’s commitment to nonviolence became stronger and deeper as the years progressed — more a personal article of faith, more spiritual, almost an end in itself. He told a gathering of farm workers during the strike: “We are engaged in another struggle for freedom and dignity with poverty denies us. But it must not be a violent struggle, even if violence is used against us. Violence can only hurt our cause.” [21] On March 17, 1966, Chávez and a group of farm workers began a 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento intending to dramatize the grape strike and get wider support. Besides its practical political and publicity value, the idea of the march was linked to sacrifice and the Mexican concept of “peregrinacion” or a religious pilgrimage. In Chávez’s terms, “this was an excellent way of training ourselves to endure the long, long struggle. … This was a penance more than anything else—and it was quite a penance, because there was an awful lot of suffering involved in this pilgrimage, a great deal of pain.” [22] In the spirit of the Lenten season, the march became a religious pilgrimage. It was planned to end on Easter Sunday. Chávez marched with the procession as it left Delano. Filipino, Mexican, Black, and Anglo members joined in enthusiastically. They carried the American and Mexican flags, the NFWA and AWOC banners, and a flag with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The march helped recruit more members, and it spread the spirit of the strike. As they passed through each small farming town in the San Joaquin Valley, hundreds of workers greeted them. Others joined the march and carried the flags to the next town. At night they had rallies with music, singing, speeches, and a dramatic reading of “El Plan de Delano” that Luis Valdez had composed. The march generated spirit. The occupants of passing cars would wave and honk if they supported the boycott and strike. Supporters of the growers would curse and make obscene gestures. Overall, there were hundreds of touching incidents of local support. In one town, a man with his daughters gave the marchers a drink of punch from a beautiful crystal bowl with cups. People working in the fields as the marchers passed by gave up their jobs and joined the procession. |

|

Photo by Cathy Murphy, Courtesy United Farm Workers

|

|

By the time the marchers had reached Stockton, a few days from their goal, there were more than 5,000 marchers singing, chanting, and waving as they walked. That night Chávez got a call from Sidney Korshak, a representative of Schenley Corporation, who said that he wanted to talk about signing a contract. César thought it was a joke and hung up. But Korshak called back, and they arranged a meeting in Beverly Hills the next day. After driving all night to get there, César found himself in Korshak’s home with representatives from the AFL-CIO and the Teamsters union. After some discussion, Korshak agreed to a recognize NFWA and sign a contract. The agreement was made public and in a triumphant mood, the pilgrimage ended a few days later on the steps of the State Capitol. They had won their first victory and demonstrated the power of their cause. This was the first time in American history that a grassroots farm labor union had gained formal recognition by a corporation. (Some years before, in Hawaii, the Longshoreman’s Union had obtained a contract for pineapple workers.) Signing a contract recognizing the union meant that the corporation had to follow certain rules about hiring, conditions of work, pay, and the use of pesticides. After three years, however, the contract was due to expire and it would have to be renegotiated. This would usually mean a new struggle with the grower to force him to recognize the union. Nevertheless, the Schenley agreement was a historic first step. |

|

The other large growers remained. The most important was the DiGiorgio Corporation. The DiGiorgios also had thousands of acres of pears, plums, apricots, and citrus trees and marketed their products under the S&W Foods and TreeSweet labels. Robert DiGiorgio, the patriarch of the family, was on the Board of Directors for the Bank of America. The DiGiorgio family had successfully broken strikes and unions since the 1930s. Chávez was convinced of the power of the boycott and soon hundreds of volunteers who remembered the previous struggles against the DiGiorgios joined the boycott drive. Within a short time, the company agreed to enter into negotiations to have an election but Chávez broke them off when company guards attacked a picketer at Sierra Vista. When negotiations finally resumed, Chávez discovered that DiGiorgio had invited the Teamsters Union to recruit among vineyard workers. Thus, beginning in mid-1966, the two unions, the Teamsters and the NFWA, began an on and off jurisdictional fight that lasted more than ten years and resulted in violence, injury, and deaths. About this time, in order to consolidate its power, the Filipino union, AWOC, and Chávez’s NFWA formally merged to form one united union within the AFL-CIO. Under the final merger agreement a new organization, called United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC) was formed with Chávez as the Director. Eventually it became the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO, or simply the UFW. The UFWOC became a full member of the AFL-CIO and as a result received millions of dollars of emergency aid during the early years of struggle. This was the first time that a predominantly Mexican union had been incorporated within mainstream organized labor. Over the years the relationship proved to be mutually supportive and the UFW never seemed to be hampered in its independence of action. From the beginning, César had not thought of La Causa as a movement that would not be motivated by appeals to race or nationality. When he had worked for the Community Service Organization, César had confronted the issue of Mexican chauvinism and had been uncompromising in fighting for the inclusion of Blacks within the organization. While the primary “core” leadership of the NFWA was Mexican American, the staff and hundreds of volunteer workers were predominantly Anglo American. During they next four years, the UFWOC grew in strength, nourished by the support of millions of sympathetic Americans who sacrificed for the farm workers. Hundreds of student volunteers lived on poverty wages in the big cities to organize an international boycott of table grapes. Scores of priests, nuns, ministers, and church members donated time, money, facilities, and energies to the farm workers’ cause. Organized labor donated millions of dollars to the UFWOC strike fund. Millions of Americans gave up eating table grapes. All this was inspired by the example of César Chávez, the soft-spoken, humble leader who quietly worked to revolutionize grower-worker relations. In 1967, the union moved from its cramped offices on Albany Street in Delano to new buildings on land they had purchased with the help of private donations and contributions from AFL-CIO affiliates. The new headquarters was located near the city dump on 40 acres of alkali land. Volunteers had built a complex of buildings including a service and administrative center, a medical clinic, and a cooperative gas station. It was called “The Forty Acres.” It became the center of the farm workers union movement in California for the next three years until the union moved its headquarters to Keane, a small town just outside of Bakersfield. On April 1, 1967 the newspapers announced the signing of a union contract between DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation and the UFWOC. The contract contained wage increases for workers and set up a special fund for health and welfare benefits. It provided for unemployment compensation and specified that hiring would be done through the union labor hall. UFWOC strikes continued against other Delano growers and by October seven new wineries had signed contracts with the union. In 1968, during one of the strikes against Guimarra Corporation, César began a fast to protest the mounting talk of violence. In characteristic fashion, he began the fast without telling anyone. He did not know how long it was going to last. On the fourth day, he decided to hold a meeting of the strikers to announce his intentions. “I told them I thought they were discouraged, because they were talking about short cuts, about violence. They were getting so mad with the growers, they couldn’t be effective anymore.”[23] After the meeting with the membership, Chávez walked to The Forty Acres. He set up his monastic cell in the storage room of the service station with a small cot and a few religious articles. Soon hundreds of farm worker families began appearing at The Forty Acres to show their support for Chávez and to attend the daily mass that he attended. A huge tent city with thousands of farm workers sprang up surrounding the gas station. There was a tremendous outpouring of emotion during the masses. Daily hundreds stood in line to meet and talk to Chávez. The national media helped make the 1968 fast a major event. As the fast went into its twentieth day, letters of support came from congressmen and senators, union and religious leaders. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sent telegrams supporting César. In one, he said, “Our separate struggles are really one. A struggle for freedom, for dignity, and for humanity.”[24] Another read, “I am deeply moved by your courage in fasting as your personal sacrifice for justice through non-violence. Your past and present commitment is eloquent testimony to the constructive power of non-violent action and the destructive impotence of violent reprisal.” [25] Dr. King was assassinated a month later. Robert F. Kennedy, who had not yet decided to run for nomination for the Presidency, also sent a telegram expressing concern for his health. Chávez would not let a doctor examine him because he felt that “Without the element of risk, I would be hypocritical. The whole essence of penance … would be taken away.” [26] When Chávez finally decided to end his fast on the twenty-fifth day, he asked Robert F. Kennedy to attend. On March 11, 1968, they held a mass at a County park with more than 4000 farm workers in attendance along with national reporters from the major papers and television networks. The mass was said on the back of a flat bed truck. César was too weak to stand and he could not speak, but Jim Drake read a message he had written earlier. It was a powerful expression of his spiritual commitment. |

|

Our struggle is not easy. Those who oppose our cause are rich and powerful, and they have many allies in high places. We are poor. Our allies are few. But we have something the rich do not own. We have our own bodies and spirits and the justice of our cause as our weapons. When we are really honest with ourselves, we must admit that our lives are all that really belong to us. So it is how we use our lives that determines what kind of men we are. It is my deepest belief that only by giving of our lives do we find life. I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally non-violent struggle for justice. To be a man is to suffer for other. God help us to be men!”[27] |

|

Over the years Chávez engaged in many other fasts, each one for a specific purpose. His followers soon learned the depth of his commitment to the principle of nonviolence so that to violate that code was to personally affront César. For the most part, his followers remained nonviolence because of Chávez’s moral authority. |

|

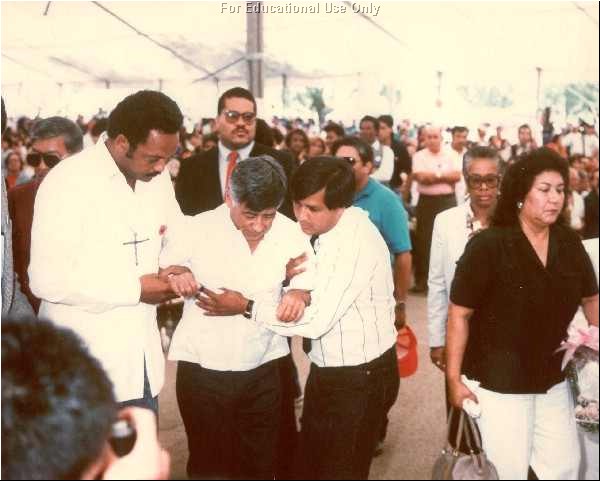

Photo by John Kouns, Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

In the late spring of 1969, the grape harvest was about to begin. To rally support for the strike and boycott César decided to organize a march through the heart of the Coachella and Imperial Valleys to the U.S.-Mexican border. One of the primary purposes of the march was to dramatize the growers’ use of undocumented immigrants from Mexico as strike-breakers. On May 10, 1969, César began the march with an outdoor mass celebrated in a labor camp in Indio. As in the 1966 march to Sacramento, the Coachella pilgrimage was a tremendous organizing tactic. Hundreds of farm workers and supporters joined in the colorful procession. Reverend Ralph Abernathy, the heir of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement, joined the march on the eighth day, pledging the support of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Walter Mondale, a liberal Senator from Minnesota who would be a future Presidential candidate, joined the march along with famous Hollywood actors and Chicano student activists. The march dramatized the strike to hundreds of Mexican workers who were in the fields as the marchers passed. In the evening masses, speeches and teatros educated them about the issues involved. The march lasted nine days and ended in Calexico, the border town across from Mexicali, Baja California where Chávez gave a speech calling for Mexican workers to join the strike and support the UFWOC. |

|

Photo by Manuel Echevarria

|

|

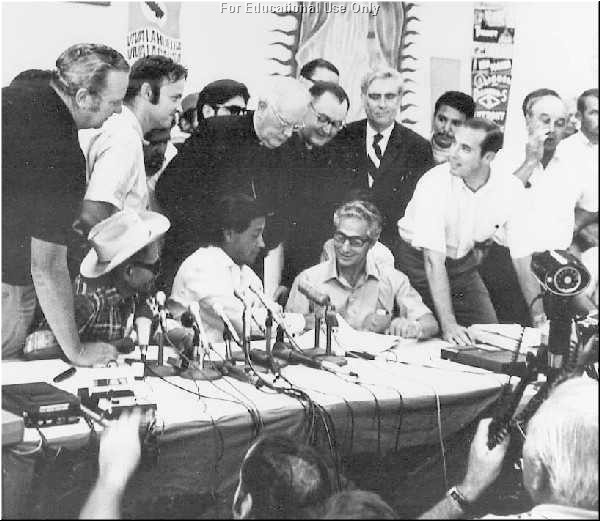

By 1969 Chávez had expanded the boycott to include all California table grapes. Throughout the country, volunteers were picketing super markets that sold grapes. Shipments of California table grapes practically stopped to the cities of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Montreal, and Toronto. Grape sales fell while millions of pounds rotted in cold storage sheds. In reaction, the growers filed a lawsuit charging that they had lost more than $25 million since the beginning of the boycott. In desperation, they turned to the Teamsters and held meetings to try to work out a contract that would bring peace to the fields. However, Teamsters were leery of entering the fields againm given their previous experience when the growers had reneged on a sweetheart deal when the pressure had become too great. Despite the support of the Department of Defense for grape purchases, the boycott pressures began to be unbearable and, gradually in the late Spring of 1969, some influential growers in the Coachella valley came to the negotiating table and signed contracts with the UFW. By June 1970, the majority of table grape growers who were still resisting unionization were in the Delano area. Finally, through the intermediaries of a committee organized by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, 23 companies, including Guimarra, agreed to begin negotiations to recognize the UFW. |

|

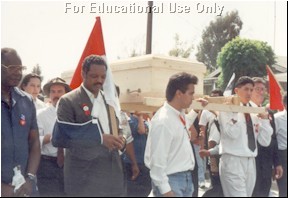

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez Foundation

|

|

On July 29, 1970, 26 Delano growers filed into Reuther Hall on The Forty Acres to formally sign contracts. César gave a short speech recalling the sacrifices that so many had made to make this moment possible and they signed the historic agreement. The contract raised the workers wages to $1.80 per hour. In addition, the growers would donate 10 cents per hour to the Robert Kennedy Health and Welfare Fund. The contract provided for all hiring to be through the union hiring hall and for the protection of workers from certain pesticides. The victory in Delano now meant that almost 85 percent of all table grape growers in California were under a union contract. This was victory without precedent in the history of American agriculture. Never before in history had an agricultural workers union managed such a sweeping success. |

|

There were indications that the farm workers were facing another formidable challenge, this time from the Teamsters and growers in the Salinas Valley, who were conspiring to undercut the UFW’s newly won recognition. Several times before, the Teamsters organization had threatened to expand their operations to organize field workers. In 1970, the Teamsters and the UFW were both members of the AFL-CIO so this announcement by the Teamsters amounted to a raid on the UFW’s jurisdiction. The Teamsters had signed sweetheart contracts giving the vegetable growers almost all that they wanted while sacrificing workers benefits. There was plenty of evidence of collusion. The Teamsters had signed the contracts without even negotiating wage rates for the workers. Quickly, Chávez moved to counter. He and the rest of the staff moved the headquarters of the union to Salinas and began organizing a strike. He traveled to the AFL-CIO convention in Chicago and attempted, with no success, to get the national organization to publicly condemn the Teamsters. Throughout the month of August, César had worked to keep the pressure on the growers with Teamster contracts by selective picketing of the largest corporations, about 170 vegetable growers who stubbornly refused to switch from the Teamsters to the UFW. This led Chávez to call for a general strike. |

|

El Macriado photo by Ben Gazzara

|

|

During this struggle with the Teamsters, César led the union to fight against a farm labor law passed by the Arizona legislature and signed by the Governor. It outlawed the boycott and limited strikes much as had been advocated by Nixon’s administration. To raise people’s awareness of the necessity to repeal the law and recall the Governor who had signed it, César began a fast in June of 1972. For 24 days César fasted and directed the recall campaign from a small room in Saint Rita’s Center in a Mexican barrio of Phoenix. Afterwards he commented on the lessons to be learned: |

| “It is possible to become discouraged about the injustice we see everywhere. But God did not promise us that the world would be humane and just. He gives us the gift of life and allows us to choose the way we will use our limited time on this earth. It is an awesome opportunity. We should be thankful for the life we have been given, thankful for the opportunity to do something about the suffering of our fellow man. … In giving yourself you will discover a whole new life full of meaning.”[28] |

|

That Fall the California growers began to try to destroy the UFW by sponsoring Proposition 22, an initiative that would outlaw boycotting and limit secret ballot elections to full time non-seasonal employees. Chávez followed the same strategy he had followed in Arizona of getting citizens registered to vote as well as informing them about Proposition 22’s threat to workers. During Fall, the “No on 22” campaign gathered momentum through the use of human billboards. On November 7, 1972, Proposition 22 was soundly defeated by a margin of 58 percent. The UFW had used the boycott organization to mobilize political support. In this election, they proved that they were a serious political force. Meanwhile the lettuce boycott and struggle with the Teamsters continued. On April 15, 1973, grape growers in the San Joaquin Valley announced that they had signed contracts with the Teamsters. César immediately called for a strike and pulled most of the UFW workers from the fields. The Teamsters recruited goons and soon violence exploded, with two union members killed. Finally, on September 1st, César decided to call off the strike and resume the boycott, which now included Gallo Winery that had signed a contract with the Teamsters. The decision to abandon the strike was motivated in part by his desire to avoid future violence, but also because he felt very deeply that the boycott would be more effective than a strike. The Teamsters finally gave up their campaign to organize field workers and take over UFW contracts in late 1974. Nevertheless, the grape and vegetable growers had contracts in place that were not set to expire for several years. Until their expiration, César had to decide on a strategy to keep his union together. He told his followers again and again of the moral values that he believed. He said |

| “There are a few basic principles that I try to follow. Don’t lie! And work hard! You can compromise on many things but not in your principles. You have to stay true to yourself. There are special guides that God gives you and you cannot trade them off. That’s a sin; then you reap what you sow. You have to use these gifts in life or you miss everything.”[29] |

|

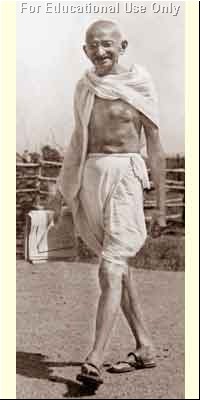

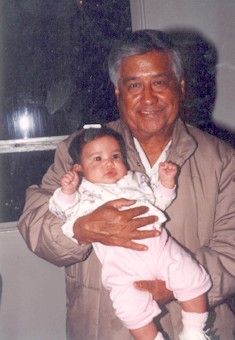

Women have always played an important, if unrecognized, role in the difficult, dangerous, and laborious struggle to organize farm labor unions. During the 1930s, Luisa Moreno worked with packing-house women and field laborers for the United Packing and Agricultural Workers of America (UCPAWA) in California. When Ernesto Galarza sought to organize the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) in the 1940s and early 1950s, he relied a good deal on the wives of farm workers for support during the long strikes. And when César Chávez set about organizing the United Farm Workers in the early 1960s, his wife, Helen, was in charge of the credit union and finances and Dolores Huerta became the Vice President in charge of negotiating contracts. Despite the generally male-dominated culture of agriculture, women within the UFW were essential for its early successes. [30] Helen F. Chávez, César’s wife, was one of the key individuals behind his success. She gave him the encouragement to pursue his dream of organizing the farm workers despite having to give up the securities of a regular paycheck to support his family. She supported his quitting his job as Director of the CSO and in turning down good paying, salaried jobs with the Government. In the early years of the union, she went to work in the fields to supplement the family income while César was organizing farm workers. She quietly took care of the eight children and volunteered to be the Treasurer for the union’s credit union. She was a traditional Mexican mother, self-sacrificing for her family and husband, choosing to avoid the public life. She joined the picket lines numerous times, and once was arrested and jailed. She was a courageous woman who said, “We never get discouraged. I guess as the years go by we get stronger. Then you want to fight extra hard.”[31] She never posed for photographs or gave speeches and has never given a formal interview. On one rare occasion, speaking with a reporter at a farm worker fiesta she said, “I want to see justice for the farm workers. I was a farm worker and I know what it is like to work in the fields.”[32] |

|

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

|

Another important woman, close to César was Dolores Huerta, Vice President of the union who shared a family with César’s brother and lived with her children at La Paz. For more than 30 years, César Chávez relied on Dolores Huerta as a confidant, adviser, and negotiator. Dolores was co-founder of the Farm Workers Association and worked as a lobbyist for the union in Washington and Sacramento. She had a strong character and was a non-traditional Mexicana, yet a loyal follower after having expressed her views. As she said, “César and I have a lot of personal fights, usually over strategy or personalities. I don’t think César himself understands why he fights with me.”[33] |

|

Because of her independence, strong personality, and total dedication to the UFW, Dolores made many personal sacrifices as she raised 11 children by herself despite her union activity. Reflecting on her non-traditional domestic life she recalled: |

| “My mother raised me and was a dominant figure in my early years. At home, we all shared equally in the household tasks. I never had to cook for my brothers or do their clothes like many traditional Mexican families. I was raised with two brothers and a mother, so there was no sexism. My mother was a strong woman and she did not favor my brothers. There was no idea that men were superior. I was also raised in Stockton, in an integrated neighborhood. There were Chinese, Latinos, Native Americans, Blacks, Japanese, Italians, and others. We were all rather poor, but it was an integrated community so it was not racist for me in my childhood.” [34] |

|

Huerta’s egalitarianism and sense of justice interacted with and influenced César. In the CSO, Dolores sent long letters to César giving him detailed accounts of her organizing activities. She gave up her paid position with the CSO to work with César in founding the FWA in Delano. There she stated, “"I like to organize. … My duties are policy making like [those of] César Chávez. It is the creative part of the organization. I am in charge of political and legislative activity. Much of my work is in public relations.” [35] Like César, she has been a public speaker, spreading the message of struggle for human justice. She recognized her key role. She said, “I know that the history of our union would have been quite different had it not been for my involvement. So I am trying to get more of our women to hang in there. The energy of women is important.”[36] Her accomplishments are many. She negotiated the first UFW contract in 1966 with the Schenley Wine Company. She oversaw the setting up of union hiring halls and helped administer union contracts once they were signed. Dolores directed the UFW’s national grape boycott and helped organize picket lines and boycotts in the 1970s. Dolores Huerta helped establish the Robert F. Kennedy Medical Plan, the Juan De La Cruz Farm Worker Pension Fund, the Farm Workers Credit Union, the first medical and pension plan, and the credit union for farm workers. Many other women have worked with César and the union over the years, and each of them has had an influence on his life. One of the many women organizers within the UFW whose contributions have yet to be recognized is Artemisa Torres Guerrero. Known as “Artie” to her co-workers, she was a key person behind the scenes helping the UFW and César Chávez achieve victory in the fields during the 1970s. César Chávez called Artie a “grandmother to the farm workers” because she volunteered all that she had to help with the boycott and strike activities in the Los Angeles area, despite her failing health. [37] During the 1970s, when Chávez arrived in the Los Angeles where she lived, he made it a point to confide in her. He discussed with her his recent activities and found out what she thought of them. Gradually by the 1980s, Artie had become Chávez’s confidant. She called him Chaperito [Shorty] and he called her “Abuelo” [Grandmother]. Other women in the UFW became part of César’s life. Mary Sanchez, Linda Legrette, Terry Vasquez Scott, and other women worked with César helping organize the complex daily life of the union. Nuns like Sister Beth Wood and Sister Betty Wolcott worked in many capacities as volunteers. Others were given tremendous responsibility and taught valuable lessons, such as Elizabeth Hernandez who reflected on César’s influence on her life: “He made me feel proud that I had attempted to work out all the problems by myself. He gave me confidence that I could do anything I set my mind to do. He gave me trust and honesty and self respect. These are the traits that I admired in him.”[38] |

|