|

Biographical Sketch

Grade Four Level

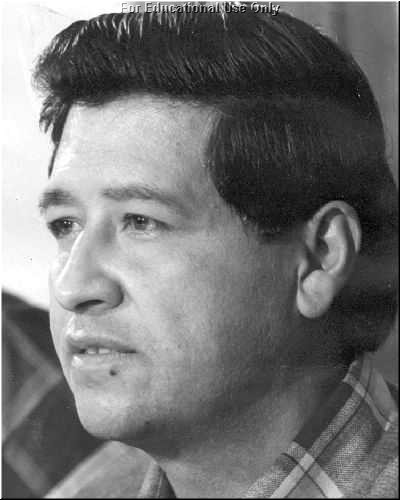

CÉSAR E. CHÁVEZ (1927-1993)

Union leader; Civil Rights Leader; Spiritual Leader; |

|

Photo Courtesy of UFW

|

|

César E. Chávez was a Latino farm worker who became a great force as a union leader, civil rights leader, environmentalist, and humanitarian. With courage, sacrifice, and hope, he provided service to others and dedicated his life to bring justice, dignity, and respect to farm workers and to poor people. He worked to improve the lives of farm workers and he led the United Farm Workers to victory in their fight for better working and living conditions. He led a nonviolent social movement to bring about change and to demand civil rights. His efforts against the use of harmful pesticides gained the support of citizens across the State of California and throughout the United States. He inspired millions of people to work and support his efforts for social change and justice. He received numerous honors for his work including the Presidential Medal of Freedom Award, the highest honor awarded to a civilian, and the creation of a holiday and day of service and learning by the State of California. |

|

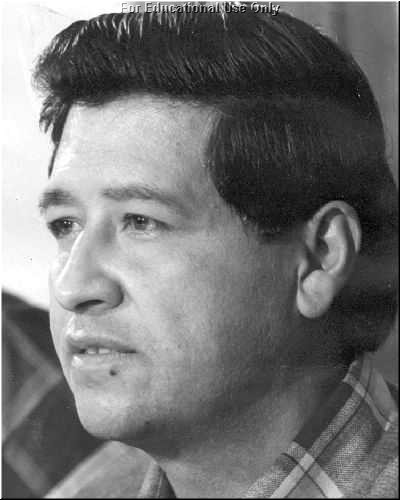

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

| César and his sister are standing outside their home. |

|

He was born in 1927 on a small farm near Yuma Arizona to Librado and Juana Chávez, and was one of six children. His grandparents had come to the United States in the 1880’s to escape the poverty of Mexico. As a child César was influenced by his mother and grandmother who taught him about kindness, feeding the hungry, nonviolence, and they also gave him a deep sense of spiritual faith. His father taught him to be a man of action that stood up for others. In 1938 during the Great Depression, César was ten years old and his family lost their land in Arizona. The family was forced to join the 30,000 migrant farm workers that traveled throughout California looking for work harvesting food in the fields. |

|

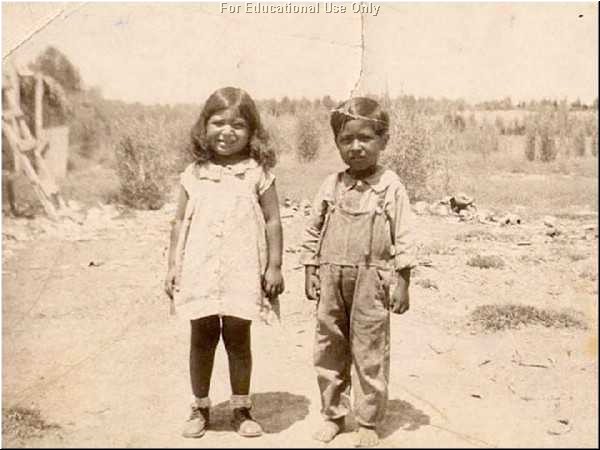

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

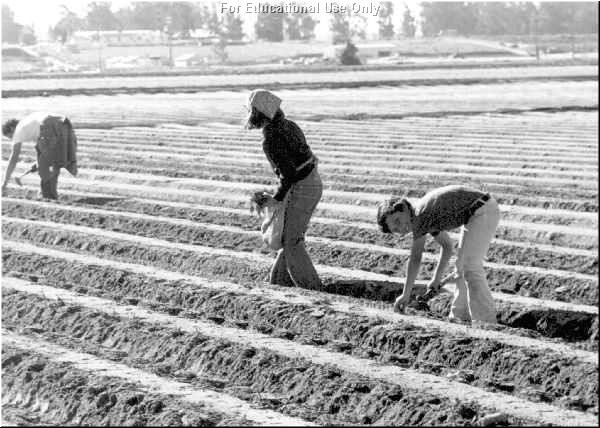

| These farm workers are picking chili in Santa Maria in 1971. |

|

“We draw our strength from the vary despair in which we find we have been forced to live. We shall endure.” César E. Chávez |

|

For ten years, César’s family traveled as migrant farm workers in California looking for work harvesting crops in the fields. They moved from town to town in order to find work. Once they found work, they had to rent run-down shacks with no heating or water from the growers who owned the land. There were so many farm workers looking for work that the growers could treat them however they wanted. If the workers complained, the growers would fire them. The Chávez family worked long hours in the fields, from 3:00 am until sunset, and were paid so little they often did not have enough money to buy food. César lived in the poverty shared by thousands of migrant farm worker families, and later said that the suffering made him strong. |

|

César experienced the pain prejudice as a small child in Arizona and later in California. César spoke only Spanish as a child, and the children at school would make fun of his accent and call him “dirty Mexican.” Teachers would hit him with rulers if he spoke Spanish in school. In California a teacher made him wear a sign around his neck, which read, “I’m a clown I speak Spanish.” When he was ten, he tried to buy a hamburger at a diner with a sign that read “white trade only.” The girl behind the counter laughed at him and told him that they didn’t serve Mexicans. César felt the pain of being treated unfairly just because he was different. This pain stood with him his entire life, and as an adult the pain shaped his commitment to make all people feel as if they were worthy human beings no matter what color they were. |

|

“There is so much human potential wasted by poverty, so many children are

forced to quit school and go to work.”

César E. Chávez

|

|

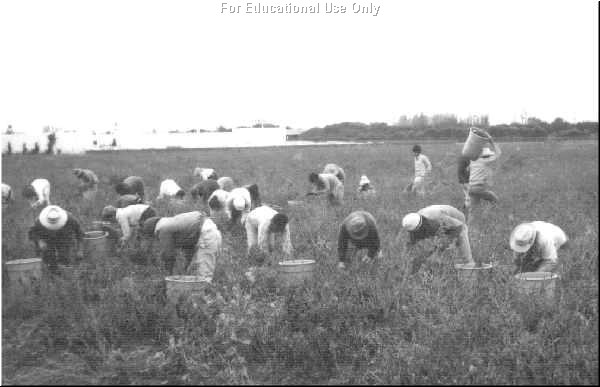

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

|

Young children worked with the family sharecropers

planting strawberries in the Santa Maria Valley in 1970. |

|

In 1942, when César was in eighth grade, his father was in a car accident and César quit school in order to work in the fields with his brother and sister. César did not want his mother to have to work. Working in the fields was very difficult. The growers demanded that farm workers use the short-handled hoe, so that workers could be close to the ground while thinning the plants; this hoe caused severe back pain. Often there was no clean water to drink or bathrooms for the farm workers to use and they had to work around dangerous pesticides. César worked long hours and felt that the growers treated farm workers without dignity as if they were not human beings and he knew this was not right. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

| César in his Navy Uniform. |

|

In 1944, César joined the United States Navy and served overseas for two years. While in the Navy he witnessed that other people suffered the pain of prejudice because they spoke different languages or were of different heritages. When he returned from the Navy he went returned to Delano to help his family work in the fields. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

| César, his wife Helen, and their six children in a family photograph. |

|

In 1948, when César was twenty-one years old, he married Helen Fabela, and together they had eight children. Helen became an important partner with César as he began to fulfill his dream of improving the lives of farm workers. |

|

Photo Courtesy of United Farm Workers

|

|

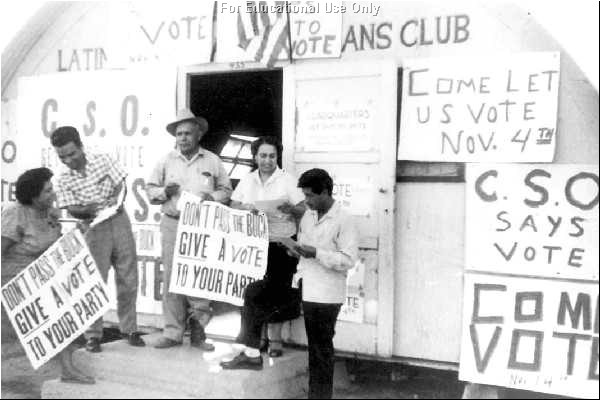

César and other Community Service Organization members

are preparing to “Get Out The Vote.” |

| “My motivation to change these injustices came from my personal life … from watching what my mother and father went through when I was growing up; from what we experienced as migrant farm workers in California.” César E. Chávez |

| In 1948, César met people and read books that would change his life forever. He met Father McDonnell who spoke to César about solving the poverty and unjust treatment of the farm worker. He asked César to read books on labor history, St Francis of Assisi, and Luis Fisher’s Life of Gandhi. From these books, César learned about the history of unions, nonviolence, sacrificing to help others, and social change, and these ideas reminded him of his family’s teachings. César said that it was at this time in his life when his real education began. |

|

In 1952, César met Fred Ross, who worked for the Community Service Organization, (CSO). Fred Ross explained how people who lived in poverty could build power for themselves and begin to help themselves. César went to work for the CSO and registered many Latino voters. César became the Director of the CSO in California. In Oxnard, California, César helped farm workers regain their jobs, but they soon lost their jobs again. César knew that the farm workers needed to form a union that would give them the power to win legal contracts that protected their rights. The CSO did not want to form a farm worker’s union, so César quit the CSO in order to be able to work and build a union for farm workers. |

| “It’s ironic that those who till the soil, cultivate and harvest fruits and vegetables and other foods that fill your tables with abundance have nothing left for themselves.” César E. Chávez |

|

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

|

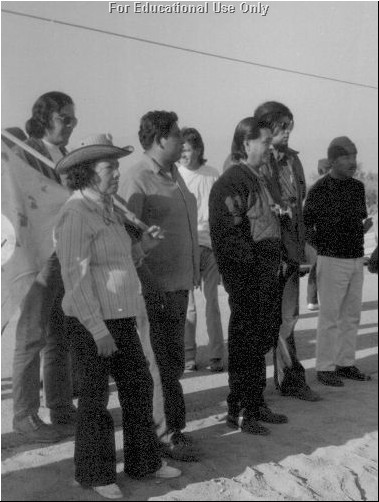

César (in the dark jacket) with farm workers on

the picket line during 1973 Grape Strike. |

|

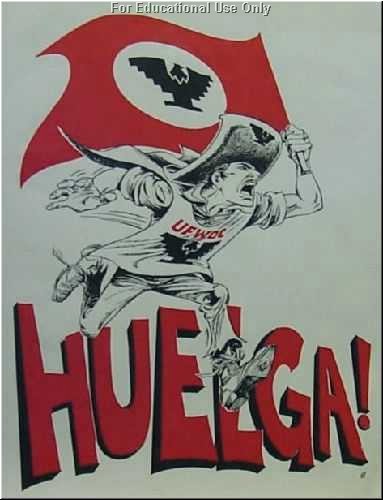

In 1962, César and his wife Helen moved with their children to Delano, California, in order to create a farm workers union. César worked for three years recruiting and teaching farm workers how to solve their problems. Since César did not earn much money while organizing farm workers, Helen worked picking grapes to support the family. The farm workers grew to trust César and many decided to join his union. César needed help and asked people to join him in Delano to help him organize and to become leaders in the union. These people came and worked without pay, and were fed by farm workers. César thought it was beautiful to be able to give up everything in order to help others. In 1962, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was born. It would later become known as the United Farm Workers (UFW). César E. Chávez was elected president, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla, vice-presidents, and Antonio Orendain, secretary-treasurer. The union adopted a flag that had a black eagle which represented the dark situation the farm worker found himself in, a white circle that signified hope, and a red background which represented the sacrifice and work the UFW would have to suffer in order to gain justice. Their official slogan was “Viva La Causa” (Long Live our Cause). César wanted to build a strong union that could fight for justice. |

|

Poster Copyright United Farm Workers

|

| United Farm Workers Organizing Committee's Huelga poster. |

| “When you have people together that believe in something very strongly, whether it be politics, unions or religion — things happen.” César E. Chávez |

|

Photo Copyright © Manuel Echavaria

|

| Strikers in the field in the early morning during the grape strike in 1973. |

| In 1965, César and the NFWA joined the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, a Filipino farm worker organization, in the famous Delano Grape Strike. The two organizations targeted the Schenley Industry, the Di Giorgio Corporation, S&W Fine Foods, and Treesweet, all growers who grew crops in the fertile fields of California and employed thousand of farm workers. The strikers wanted contracts that would force the growers to follow certain rules regarding hiring, better working conditions, better pay, and control of pesticides. They also wanted the growers to give them respect and dignity in the fields. The growers did not want to spend money on the improvements, so they growers fought the strike. |

| The two farm worker organizations joined to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC). When UFWOC went on strike, the members refused to work and they picketed the fields with signs and flags trying to get other workers in the fields to join the strike. The growers brought in strikebreakers to harass the picketers, sprayed the picketers with pesticides, and used shotguns and dogs to frighten them. Most of the strikers remained on the picket lines, and César reminded them constantly that they were not to use violence of any kind. César said that nonviolence was more powerful than violence, and that it was the only way to win peace and justice. César taught the union members how to react and act peacefully, even when the growers used violence against the strikers. César had studied Gandhi’s use of the power of nonviolence in his struggle for social justice in India, and César deeply believed that the strike would have to be one of nonviolence if they were to win. |

| “There is no turning back. We are winning because ours is a revolution of the mind and the heart.” César E. Chávez |

|

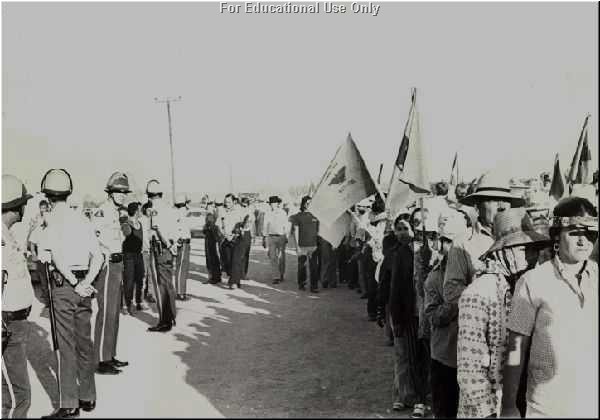

Photo Copyright, El Macriado

|

| Picket line at grape strike in Coachella in 1973. |

|

Hundreds of people of all colors and faiths came to Delano to help with the grape strike. Many churches of all different faiths supported the strike. César thought that all religions were very important and he welcomed their support. The national media (television crews, news papers reporters, and writers for magazines) covered the use of violence by the growers against the nonviolent striking farm workers. NBC aired a documentary called “The Harvest of Shame” that showed how farm workers were forced to live in poverty. Millions of Americans and political leaders saw that César was fighting for the justice that America promises all of its citizens. Other labor unions supported the strike. César called for a national boycott of grapes, during a boycott the growers loose money because in a boycott people stop buying the food that the growers sell in the supermarkets. Eventually the growers are forced to negotiate with the farm workers. César believed that the American people had a sense of justice and he was right. Millions of Americans supported the boycott and stopped buying grapes because they understood the injustices that the farm workers suffered. |

| “There is enough love and good will in our movement to give energy to our struggle and still have plenty left over to break down and change the climate of hate and fear around us.” César E. Chávez |

|

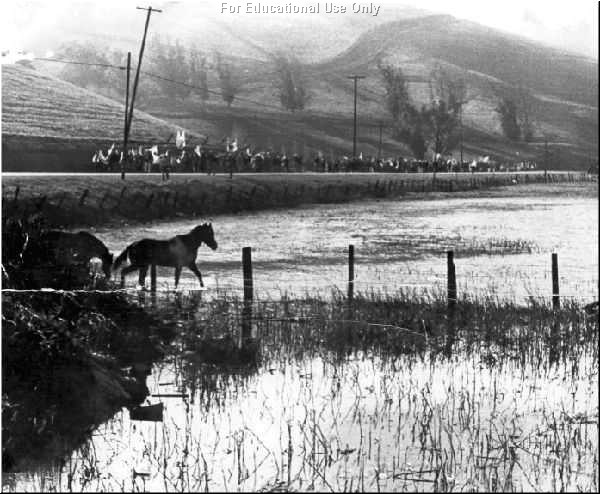

Photo Copyright, El Macriado

|

| Farm workers and other supporters march past a field on their way to Stockton. |

| In 1966, César organized a 340-mile march from Delano to Sacramento, California, in order to get support for the strike from the public, other farm workers and the Governor. Although César’s feet were swollen and bleeding, he continued to march. When the march reached Stockton it had grown to 5,000 marchers, it was then that the growers contacted César and agreed to recognize the union and sign a labor contract that would promise better working conditions and higher wages. This was the first contract ever signed between growers and a farm worker’s union in the history of the United States, but César’s work had just begun. |

| “The fast is a very personal and spiritual thing, and it is not done out of recklessness. It’s not done out of a desire to destroy yourself, but it is done out of a deep conviction that we can communicate with people, either those that are for us or against us, faster and more effectively spiritually than any other way.” César E. Chávez |

|

Photo by John Kouns, Courtesy of César E.

Chávez Foundation

|

|

César breaking his fast with Robert Kennedy,

UFW supporters, his wife Helen, and his mother Juana. |

| In 1968, César went on the first of three public “fasts” to protest the violence that was being used on both sides of the strike. When César fasted, he would stop eating in order to gain spiritual strength and communicate with people on a spiritual level. People from all over the United States felt the importance of his fasts; his quiet sacrifice spoke to many people about the injustice that existed for farm workers. In 1968 when he ended his fast, 8,000 people including Robert Kennedy were there to support him. The media would cover his fasts and he would receive letters of support from politicians, religious leaders, and civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. |

| “Our struggle is not easy. Those that oppose our cause are rich and powerful, and they have many allies in high places. We are poor. Our allies are few. But we have something the rich do not own. We have our own bodies and spirits and the justice of our cause as our weapons.” César E. Chávez |

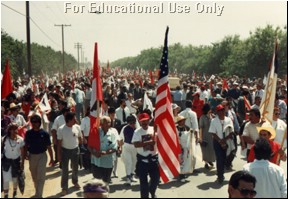

| César had won his first contract, but there were still many growers in California who had not recognized the UFW, (formerly the UFWOC) and for the next four years, the union continued to nonviolently strike against the growers. The UFW continued to grow in strength because of the national boycott. It also grew because César built a national coalition of students, middle-class consumers, trade unionists, religious groups, and minorities including: Latin Americans, Filipinos, Jews, Native Americans, African Americans, gays and lesbians. César's quiet dedication and sacrifice had inspired many to help the UFW. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. sent César a telegram stating that he and César were united because they both had the same dream for a better tomorrow. By 1970, 85% of all the growers in California had signed contracts with the UFW. César E. Chávez, a gentle man of vision, had worked to revolutionize the relationship between growers and farm workers. He had started a nonviolent movement that demanded civil rights and economic justice. |

| “You and your valiant fellow workers have demonstrated your commitment to righting grievous wrongs forced upon exploited people. We are together with you in spirit and determination that our dreams for a better tomorrow will be realized.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. |

|

Photo Copyright © Jocelyn Sherman

|

| César marching in support of the grape boycott. Martin Sheen is on the left. |

|

From 1970-1980, César and the UFW continued to boycott and strike for

farm workers’ rights and the control of dangerous pesticides that are

sprayed on crops. Although César won many victories, the struggle for

justice, fair treatment, respect, and dignity were always in jeopardy. However,

César never gave up. He kept working and had faith that people united

could create a better world. In 1975, due to César's efforts, the

Supreme Court outlawed the short-handed hoe that had injured the backs of

thousands of farm workers that were forced to use it. In June of 1975, the UFW

sponsored a farm-labor law with the support of growers. Governor Brown signed

into law the Agricultural Labor Relations Act that gave farm workers the right

to organize a union and hold to elections. The Agricultural Labor Relations Act

remains the strongest law nationwide protecting the rights of farm workers. By

1978, the union had 100,000 members and had won a contract with the largest

lettuce grower in the United States.

In the 1980s, César traveled to the midwest and the eastern states in order to teach people about the dangers of the pesticides being sprayed on crops. The pesticides caused cancer and birth defects in the children of farm workers. César went on a 36-day fast for “fast for life” to draw attention to the harmful effects of pesticides. Thousands of people supported him by continuing his “fast for life” in 3-day contributions that were passed on from one person to another. In the end, the growers listened to his concerns and began reviewing their use of pesticides. The State of California also revised its use of pesticides because of his efforts. |

|

Photo Courtesy of United Farm Workers

|

|

A crop duster is spraying a field in Delano with pesticides,

while farm workers are working in the field in 1969. |

| In the 1990s, César recovered from his fast and continued to boycott of grapes. In 1992, he received an honorary Doctorate Degree from Arizona State University and attended graduation ceremonies. He was very proud of the honor because he believed that education is very important, and his dream was that all children should have the opportunity to get a quality education. |

|

Photo Copyright © Jocelyn Sherman

|

| Many people came to César’s funeral. |

| César E. Chávez worked right up until the night he died peaceful in his sleep. He died on April 23, 1993 in San Luis, Arizona. He was in Arizona helping lawyers fight a lawsuit against he UFW. His funeral was held on April 29, 1993 in Delano, California, and more than thirty thousand people followed his simple pine casket for three miles. It was their last opportunity to march with a humble man of great strength and vision that had bettered the lives of many people. |

| “Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot uneducated the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the person who is not afraid anymore. We have looked into the future and the future is ours.” César E. Chávez |

|

Photo by Ann Benson, Courtesy United Farm Workers

|

| César and young volunteers are sitting on the steps with his dog, Huelga. |

| César E. Chávez will be remembered as a leader and for his dedication to justice, nonviolence, and service to others. He is an American hero who will continue to inspire people to respect life, stand up for justice, and to work together for the good of humanity. |

|

Photo Courtesy of César E. Chávez

Foundation

|

|

Helen Chávez is accepting César’s Presidential Medal of

Freedom

from President Bill Clinton at the White House ceremony. |

| The State of California has declared César E. Chávez’s birthday, March 31, a State Holiday to celebrate his life and work. In the spirit of César E. Chávez Day, public schools in the State of California will teach service to others and celebrate the life and work of César E. Chávez. In 1994, President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded César E. Chávez the Presidential Medal of Freedom Award, the highest civilian award. Helen Chávez accepted the honor at the White House in Washington, DC. In 1990, César was awarded the Aguila Azteca, the highest civilian award by the Mexican government. In 1992, he was granted an honorary Doctorate by the University of Arizona. Many schools and streets are so named to honor the legacy of César E. Chávez. |

|

Griswold del Castillo, Richard and Richard A. Garcia. César Chávez: A Triumph of Spirit Susan Ferriss and Ricardo Sandoval, The Fight in the Fields: César Chávez and the Fight in the Fields Jacques E. Levy, César Chávez: Autobiography of La Causa |